The myth of the protocols

In 1919, one of Germany's senior military leaders, Erich Ludendorff, declared the Jews were one of several groups to blame for the country's downfall.

By 1922, he was almost totally focused on Jews as "the enemy." "The supreme government of the Jewish people worked hand in hand with France and England," he said. “Perhaps it was leading them both."

He referenced the Protocols of the Elders of Zion as evidence, a document allegedly holding the minutes of a secret meeting of Jewish leaders—the so-called "Elders of Zion"—held around the turn of the twentieth century.

The "Elders" supposedly conspired to take over the world at that alleged conference.

In actuality, the Protocols are a hoax; it was written in the early 1900s by Russian secret police to promote hatred against Jews. Few people paid any attention to the document at the time, but it became an international sensation after the end of the First World War.

Many people felt that the Protocols explained "inexplicable" events like the war, the economic crises that followed it, the uprisings un Russia and Central Europe, and even plagues. Myths about a "Jewish conspiracy" have existed for millennia, but the Protocols gave them fresh life, even after the paper was revealed to be a forgery in 1921. Many people believed that the war and the earth-shattering events that followed validated the Protocols' veracity, regardless of the evidence presented to the contrary.

The creators of the Protocols plagiarised extensive passages from various fictional works to generate the document, according to the Times of London in August 1921.

As a result of the exposé, the British business that originally produced the English version of the Protocols refused to print or distribute additional copies, and some newspapers stopped covering the story. Neither measure, however, harmed the Protocols' popularity.

Attempts to disprove a lie have been found in recent years to leave people more convinced than ever that the lie is true.

International Exposure

Long after the Times exposé, the Protocols acquired a following in every country.

- In 1924, a Japanese edition was issued.

- The following year, an Arabic translation was published.

- The patriarch of Jerusalem (the leader of the Eastern Orthodox Church in Palestine) encouraged churchgoers to purchase the book.

- Henry Ford, the American automaker, went one step farther. He serialised the manuscript in his weekly newspaper in 1920, then published hundreds of articles and books based on its contents. (Although Ford later withdrew his support for the Protocols as part of a legal settlement, the damage had been done.)

Long after Ford stopped publishing and distributing the paper, hundreds of antisemites in the United States continued to do so.

Weimar republic

In the 1920s, Germany's 500,000 Jews constituted less than 1% of the overall population of approximately 61 million people. However, by focusing on Jews as "the enemy," antisemites created the impression that Jews were everywhere and were to blame for everything that went wrong in the country.

The falsehood that Jews were responsible for the "stab in the back" at the end of the war, the Treaty of Versailles, the Communist Party, and the establishment of the Weimar Republic was promoted by Ludendorff and others.

As a result, the destruction of the Weimar Republic must be the first step in "rescuing" Germany from a "Jewish conspiracy," according to this viewpoint. A number of radical parties hired thugs and formed private armies to assassinate republic supporters.

Walter Rathenau

Many extremist groups focused on Germany's foreign minister, Walter Rathenau, a wealthy Jewish businessman, writer, and thinker. He worked with the German War Ministry during the war to guarantee that the military had enough food and other resources.

Without his efforts, Germany would have most likely lost the war much earlier. Nonetheless, when he was named Foreign Minister in 1922, many Germans were angry. Never before had a Jew occupied such a powerful role in German politics.

Rathenau was assassinated on his way to work on 24th June 1922. The two gunmen and their accomplices were military veterans affiliated with extreme nationalist organisations. In July, police finally apprehended them and executed one of the assassins; the other committed suicide. The government then tried the 13 surviving conspirators. The guys did not deny murdering Rathenau, but they maintained that the assassination was legitimate since Rathenau was a so-called "Elder of Zion."

Hyperinflation

Germans looked for someone to blame for the crisis during the year of hyperinflation. There was a common belief that a few people were becoming wealthy while honest employees went hungry. Who was to blame? Many Germans saw the Jews as the answer, despite the fact that they, too, were victims of hyperinflation.

Following a review of German census data, historian Donald L. Niewyk discovered that, while a few Jews were extremely successful and wealthy in Germany at the time, the vast majority were not. "By the end of 1923, the Berlin Jewish Community had created nineteen soup kitchens, seven shelters, and an employment information and placement agency for the city's needy Jews," he stated. “Other big-city communities followed suit."

In fact, the people who suffered the most during Hyperinflation were Jewish refugees from Russia and other eastern and central European countries who had fled to Germany after the war to avoid persecution and upheavals in their home countries. These Jews served as an easy target for increased antisemitism, and they faced "chronic unemployment, intermittent state harassment, and the hostility of both Jewish and non-Jewish Germans."

On 5th November 1923, at a period when the German mark was nearly worthless, increasing anti-Jewish sentiment erupted into violence. An enraged mob trashed the homes and shops of Jewish refugees in a Berlin neighbourhood for two days, according to a newspaper reporter:

Nazi persecution

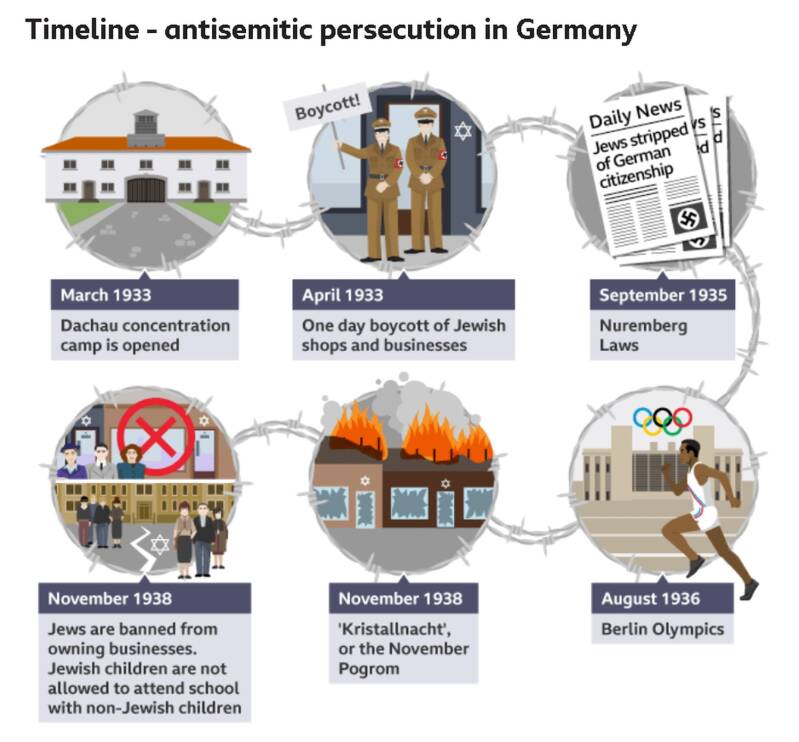

Key events in Germany relating to the persecution of the Jews: 1933 - 1938.