A German pogrom

Kristallnacht, also known as the "Night of Broken Glass," was a pogrom that took place in Germany and Austria on November 9th and 10th in 1938.

This event marked the beginning of the systematic persecution of Jews by the Nazi regime and was a turning point in the history of the Holocaust.

The events of Kristallnacht were sparked by the assassination of a German official, Ernst vom Rath, by Herschel Grynszpan, a young Jewish man.

In response, the Nazi Party organized a coordinated attack against Jewish communities throughout Germany and Austria, during which synagogues were burned, homes and businesses were vandalized, and thousands of Jews were arrested and sent to concentration camps.

The name "Kristallnacht" refers to the shards of broken glass that littered the streets from the widespread destruction of Jewish-owned storefronts and homes.

This synagogue, which is bearing a sign reading "Germans, do not buy from Jews," was burned in the Kristallnacht attacks.

Getty Images

Photos of Kristallnacht, the 'Night of Broken Glass,' on Its 81st Anniversary (insider.com)

Oppression of the Jews

In the 1920s, most German Jews were fully integrated into German society as German citizens. They served in the German army and navy and contributed to every field of German business, science and culture.

Conditions for German Jews began to worsen after the appointment of Adolf Hitler as Chancellor of Germany on 30 January 1933, and the implementation of the Enabling Act on the 23rd of March 1933 after the Reichstag Fire a month earlier. This allowed Hitler to increase his grip on power in Nazi Germany.

Nazi propaganda alienated 500,000 Jews in Germany, despite the fact that they constituted only 0.86% of the total population, by framing them as the enemy responsible for Germany's defeat in the First World War and subsequent economic disasters, such as the 1920s hyperinflation and subsequent Great Depression.

Würzburg, Germany, 11 March 1933. A demonstration of several hundred Würzburg residents against Jewish businesses.

Yad Vashem Photo archives

The Jews of Würzburg (Germany) During the Holocaust, 1933-1938 (yadvashem.org)

Beginning in 1933, the German government enacted a series of anti-Jewish laws that limited German Jews' ability to earn a living, enjoy full citizenship, and obtain an education, including the Law for the Restoration of the Professional Civil Service of 7 April 1933, which prohibited Jews from working in the civil service.

The Nuremberg Laws of 1935 deprive German Jews of their citizenship and forbid Jews from marrying non-Jewish Germans.

Three members of the Nazi SA stand outside a Jewish-owned business during the boycott of shops. Their signs have intimidating and offensive slogans that read, ‘Germans! Defend yourselves! Do not buy from Jews!’

As a result of these laws, Jews were excluded and alienated from German social and political life. Many sought asylum abroad, and over 250,000 Jews fled Germany and Austria, which Germany had annexed in March 1938; more than 300,000 German and Austrian Jews sought refuge and asylum from oppression.

Some historians believe that the Nazi government was planning an outbreak of violence against Jews and was waiting for the right provocation; evidence of this planning dates back to 1937.

The desire of the NSDAP Gauleiters to seize Jewish property and businesses, according to German historian Hans Mommsen, was a major motivation for the pogrom.

Würzburg on "Boycott Day ", 1 April 1933. An SS man stands in front of a Jewish business, which is blocked by a sign calling shoppers to boycott the store. The sign reads: "Fight the [Jewish] Department Stores ".

Yad Vashem Photo archives

The Jews of Würzburg (Germany) During the Holocaust, 1933-1938 (yadvashem.org)

Expulsion

In August 1938, German authorities announced that foreigners' residence permits would be revoked and would have to be renewed. This included German-born Jews with dual nationality. Additionally, Poland stated that after the end of October, it would renounce citizenship rights to Polish Jews living abroad for at least five years, effectively rendering them stateless. So if you were a Polish Jew who had lived in Germany for more than five years, you were effectively screwed.

On Hitler's orders, more than 12,000 Polish Jews were expelled from Germany on October 28, 1938 in an event know as ‘Polenaktion’. They were ordered to leave their homes in a single night and were only permitted to bring one suitcase per person. They were taken from their homes to railway stations and loaded onto trains bound for the Polish border, where Polish border guards returned them to Germany. This stalemate lasted for days in the pouring rain, with Jews marching between the borders without food or shelter. Four thousand people were allowed to enter Poland, but the remaining 8,000 were forced to remain at the border.

At the end of October, 1938, thousands of Polish Jews in Germany were forcibly repatriated by the Nazis and housed in military barracks in Zbaszyn, Poland.

20 Amazing Black and White Photographs of Jewish Life From the 1930s ~ Vintage Everyday

They waited in harsh conditions for permission to enter Poland. According to a British newspaper, hundreds "are reported to be lying around, penniless and deserted, in little villages along the border near where they were driven out by the Gestapo and left." They existed in appalling conditions and some who tried to re-enter Germany were shot.

Amongst the stranded Jews were family of Sendel and Riva Grynszpan, whose son, Herschel, was seventeen years old and living in Paris with an uncle. Herschel received a postcard from his family at the Polish border, detailing their expulsion.

Four days after receiving the postcard, he went out and bought a gun…

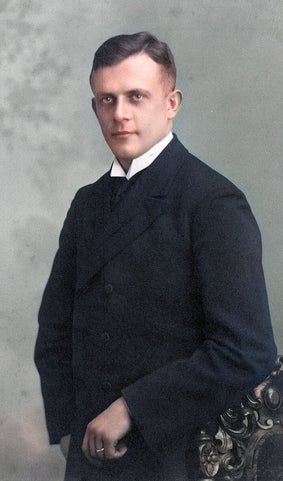

Eduard von Rath

Ernst Eduard vom Rath (June 3, 1909 – November 9, 1938) was a German nobility member, Nazi Party member, and German Foreign Office diplomat.

Vom Rath was born into an aristocratic family in Frankfurt am Main, the son of a high-ranking public official, Gustav vom Rath.

He went to a Breslau school before studying law in Bonn, Munich, and Königsberg until 1932, when he joined the Nazi Party and became a career diplomat.

In April 1933, he joined the SA, the party's paramilitary unit. Following a posting in Bucharest, he was assigned to the German embassy in Paris in 1935.

Regarding the "Jewish Question," Rath expressed regret that German Jews had to suffer but argued that anti-Semitic laws were "necessary" in order for the Volksgemeinschaft to thrive.

Herschel Grynszpan

Grynszpan after his arrest, 1938.

Creative Commons — Attribution-ShareAlike 3.0 Germany — CC BY-SA 3.0 DE

Herschel Feibel Grynszpan was a Polish-Jewish immigrant who grew up in Weimar, Germany.

Grynszpan was thought to be intelligent, if rather lazy, by his teachers, a student who never seemed to try to excel at his studies. He later claimed that his teachers disliked him because he was an Ostjude (‘Eastern Jew’ – they were considered less assimilated into German society than German Jews), and that he was treated as an outcast by both his German teachers and his classmates.

Grynszpan was known as a child and teenager for his violent temper and tendency to respond to antisemitic insults with his fists, and he was frequently suspended from school for fighting.

Instead, he and his parents decided to relocate to Paris and live with his uncle and aunt, Abraham and Chawa Grynszpan. Grynszpan obtained a Polish passport and a German residence permit before leaving Germany for Belgium, where another uncle lived.

He did not intend to stay in Belgium and illegally entered France in September 1936. (Grynszpan could not legally enter France because he lacked financial support; Jews were not allowed to take money from Germany.)

He lived in a small Yiddish-speaking enclave of Polish Orthodox Jews in Paris. Outside of it, Grynszpan met few people and learned only a few words of French in two years. He began his life as a carefree, bohemian "poet of the streets," wandering aimlessly and reciting Yiddish poems to himself.

However, he was unable to legally become a resident of France, could not return to Germany as re-entry permit expired in April 1937 and his Polish passport expired in January 1938, leaving him without papers.

The Jewish quarter in Paris, 1930's.

Jewish quarter of Paris before World War II | Holocaust Encyclopedia (ushmm.org)

In July 1937, the Paris Police Prefecture ruled that he had no legal basis to remain in France, and he was ordered to leave the following month. Grynszpan didn't want to go back to Germany.

Poland passed a law in March 1938 that stripped Polish citizens who had lived continuously abroad for more than five years of their citizenship.

As a result, Grynszpan became stateless and continued to live illegally in Paris. As his situation worsened, he became increasingly desperate and angry, living in poverty on the outskirts of French life as an illegal immigrant with no real skills.

This angry, homeless young Jew and the aristocratic, antisemitic German aristocrat would soon cross paths with bloody results.

The assassination

On the morning of November 7, 1938, after learning of his parents' deportation from Germany to the Polish border. Herschel Grynszpan, a Polish-German Jew, went to the German embassy in Paris and asked to speak with an embassy official.

Grynszpan calmly approached the reception desk and asked to speak with a member of the embassy about a secret document of great value that he was willing to divulge. Ernst vom Rath's office, a 29-year-old diplomat, was shown to him.

When vom Rath asked to see his secret document, Grynszpan reportedly stood up and said:

He then fired all five bullets at vom Rath, hitting him twice. The price tag for the gun was still dangling from the trigger. Vom Rath, 29, was fatally wounded with bullets to the spleen, stomach, and pancreas.

A 17-year-old Herschel Grynszpan under arrest for the murder of German diplomat Ernst vom Rath.

Staff/AFP/Getty Images

Adolf Hitler personally dispatched his two best doctors, personal physician Karl Brandt and surgeon Georg Magnus, to Paris in an attempt to save vom Rath's life. Hitler promoted vom Rath, a junior officer at the embassy, to the rank of Legal Consul, First Class just hours before his death on 9th November. Within hours, Kristallnacht had begun.

After his arrest, Grynszpan claimed he shot Ernst vom Rath five times in retaliation for the thousands of Jewish refugees, including members of his own family, who had been expelled from Germany and were trapped in horrific conditions at the Polish border.

The funeral of Ernst vom Rath.

The night of the broken glass

With the death of Vom rath, violence was soon to follow.

Hitler learned of his death that evening while attending a dinner commemorating the 1923 Beer Hall Putsch with several key members of the Nazi party. Following heated debate, Hitler abruptly left the assembly without delivering his usual address.

In his place, Propaganda Minister Joseph Goebbels delivered the speech, saying that "the Führer has decided that... demonstrations should not be prepared or organized by the party, but insofar as they erupt spontaneously, they are not to be hampered."

SS chief Reinhard Heydrich sent an urgent secret telegram to the Sicherheitspolizei and the Sturmabteilung (SA) on November 10, 1938, at 1:20 a.m., containing instructions regarding the riots.

SS chief Reinhard Heydrich who instructed German police not to intervene during Kristallnacht.

Baden Baden, Germany - arrest of Jews by the SS on Kristallnacht.

Remembering the November 1938 Pogrom ("Kristallnacht"): Holocaust memorial ceremony (yadvashem.org)

This included guidelines for the protection of non-Jewish businesses and property owned by foreigners. Police were told not to intervene in the riots unless the guidelines were broken. Police were also told to seize Jewish archives from synagogues and community centres, as well as to arrest and detain "healthy male Jews who are not too old" for eventual transfer to (labour) concentration camps.

The chief party judge, Walter Buch, later stated that the message was clear; Goebbels had ordered the party leaders to organise a pogrom with these words.

Gestapo Chief Heinrich Müller stated in a message to SA and SS commanders that the "most extreme measures" would be taken against Jews.

The SA and Hitler Youth shattered the windows of approximately 7,500 Jewish stores and businesses, giving rise to the name Kristallnacht (Crystal Night), and looted their contents.

Throughout Germany, Jewish homes were ransacked. Although the authorities did not explicitly condone violence against Jews, there were reports of Jews being beaten or assaulted.

Suicides and rapes were reported in large numbers by police departments in the aftermath of the violence.

A Synagogue ablaze during Kristallnacht.

Furniture and ritual objects from the synagogue in Mosbach on the town square on November 10, 1938.

Fine Art Images/Heritage Images/Getty Images

Photos of Kristallnacht, the 'Night of Broken Glass,' on Its 81st Anniversary (insider.com)

The Manchester Guardian, 12 November 1938.

From the archive: Kristallnacht | Kristallnacht | The Guardian

Rioters destroyed 267 synagogues in Germany, Austria, and the Sudetenland. Over 1,400 synagogues and prayer rooms, numerous Jewish cemeteries, over 7,000 Jewish shops, and 29 department stores were damaged or destroyed.

More than 30,000 Jewish men were arrested and imprisoned in Nazi concentration camps, primarily Dachau, Buchenwald, and Sachsenhausen.

Flames pouring out of a synagogue in Siegen, Germany, during Kristallnacht.

Remembering the November 1938 Pogrom ("Kristallnacht"): Holocaust memorial ceremony (yadvashem.org)

The synagogues, which date back centuries, were also victims of significant violence and vandalism, with the tactics used by the Stormtroopers on these and other sacred sites described as "approaching the ghoulish" by the US Consul in Leipzig.

Tombstones were desecrated, and graves were desecrated. Prayer books, scrolls, artwork, and philosophy texts were thrown into the fires, and valuable buildings were either burned or smashed until unrecognisable.

Persecution of Jews in the center of the city during Kristallnacht.

Remembering the November 1938 Pogrom ("Kristallnacht"): Holocaust memorial ceremony (yadvashem.org)

Aftermath

A wrecked Jewish storefront - a victim of the Kristallnacht.

Reflecting on Kristallnacht 78 Years Later (facinghistory.org)

Persecution and economic damage were inflicted on German Jews after the pogrom, even as their businesses were ransacked.

They were forced to pay a collective fine or "atonement contribution" of one billion Reichsmarks for the murder of vom Rath (equivalent 7 billion dollars in 2020), which was imposed by the state's compulsory acquisition of 20% of all Jewish property.

Six million Reichsmarks of insurance payments for property damage due to the Jewish community were instead paid to the Reich government as "damages to the German Nation".

Jews were forced to pay for all damages caused by the pogrom to their homes and businesses.

A worker clearing broken glass of a Jewish shop following the anti-Jewish riots of Kristallnacht in Berlin.

Hulton Archive/Getty Images

Kristallnacht …. Horror Night Of November 9, 1938!! | It Is What It Is (wordpress.com)

The aftermath of Kristallnacht.

US Holocaust Museum

10 Kristallnacht Photos That Capture the Horror of 'The Night of Broken Glass' - HISTORY

The number of Jews emigrating increased as those who could left the country did. Over 115,000 Jews emigrated from the Reich in the ten months following Kristallnacht. The vast majority went to other European countries, the United States, and Mandatory Palestine, with at least 14,000 arriving in Shanghai, China.

The Nazis seized houses, shops, and other property left behind by émigrés as part of government policy. Many of the shattered remains of Jewish property looted during Kristallnacht were disposed of near Brandenburg.

A Jewish owned shop daubed with graffiti after Kristallnacht.

Reaction in Germany

Non-Jewish Germans reacted differently to Kristallnacht. Many people gathered on the scene, most of them silently. To prevent the flames from spreading to neighbouring buildings, the local fire departments confined themselves. In Berlin, police Lieutenant Otto Bellgardt prevented SA troopers from setting fire to the New Synagogue, earning him a verbal reprimand from the commissioner.

The extent of the damage caused by Kristallnacht is said to have outraged many Germans, who described it as senseless. However, Adolf Hitler, the German leader, made no personal comments or even acknowledged Kristallnacht.

Hitler was conspicuous by his lack of comments on the events of Kristallnacht, choosing isntead to stay silent on the issue.

. In this photo, taken on the day Kristallnacht began, Hitler and several high-ranking Nazi officials are captured commemorating the 15th anniversary of the 1923 Beer Hall Putsch. The Beer Hall Putsch, also known as the Hitlerpusch, was Hitler's attempt to stage a coup in Bavaria.

Getty Images

Photos of Kristallnacht, the 'Night of Broken Glass,' on Its 81st Anniversary (insider.com)

In 1938, shortly after Kristallnacht, psychologist Michael Müller-Claudius interviewed 41 Nazi Party members at random about their attitudes towards racial persecution. Sixty-three percent of the interviewed party members expressed outrage, while only 5% approved of racial persecution, with the rest remaining undecided. A 1933 study found that 33% of Nazi Party members had no racial prejudice, while 13% supported persecution.

According to academics like Sarah Ann Gordon, there are two possible explanations for this disparity. The first is that, by 1938, a large number of Germans had joined the Nazi Party for pragmatic rather than ideological reasons, diluting the percentage of rabid antisemites; for many, it was simply safer to be on the inside looking out, rather than the outside looking in.

Members of the Nazi Party salute at a rally in Czechoslovakia in May 1938. Many members of the Nazi party were against, or even horrified, by the events of Kristallnacht.

Getty

Secondly, Kristallnacht may have caused party members to reject antisemitism that had been acceptable to them in abstract terms but that they could not support when it was concretely enacted.

It’s one thing to say you simply don’t like a particular group of people – particularly if you don’t have any personal connection with them and are not required to examine your view further. It’s quite another to witness them being terrorised, their property destroyed, and many being arrested and shipped off. Being suddenly witness to such brutal, unprovoked violence would have shaken many Germans, regardless of their political views.

In fact, several Gauleiters and deputy Gauleiters even refused orders to carry out the Kristallnacht, and many leaders of the SA and the Hitler Youth openly refused party orders while expressing disgust.

During Kristallnacht, some Nazis even assisted Jews. This second point helps illustrate that for all his power and influence, even Hitler couldn’t push his supporters indefinitely. Many of them – even his most devout followers - had their limits.

The persecution of the Jews wasn’t a sudden, catastrophic bombshell but a steady incremental increase in hostility and violence over the course of a few years. And in 1938, there were still plenty of Germans who would recoil at the thought of racially motivated violence being inflicted on others.

The synagogue at Oranienburger Straße 30 was spared from destruction thanks to the actions of the local police and fire services.

Neue Synagoge (Oranienburger Straße 30) - Retro photos (pastvu.com)

Reflecting this – and to the Nazis' chagrin - Kristallnacht had the opposite effect on public opinion than what they had intended; the peak of opposition to Nazi racial policies was reached just then, when, according to almost all accounts, the vast majority of Germans rejected the violence perpetrated against Jews.

Verbal complaints increased rapidly, and the Düsseldorf branch of the Gestapo, for example, reported a sharp decline in anti-Semitic attitudes among the population.

Religious opposition

There are numerous indications of Protestant and Catholic opposition to racial persecution; for example, in 1934, anti-Nazi Protestants adopted the Barmen Declaration, and the Catholic church had already distributed pastoral letters critical of Nazi racial ideology, and the Nazi regime expected to face organised resistance from it following Kristallnacht.

However, the Catholic leadership, like the various Protestant churches, refrained from taking organised action and churches as a whole chose public silence – probably stunned by the level of overt violence on display during Kristallnacht. Witnessing the Nazis actively single out and attack a major religious group probably provoked a sense of unease amongst the Christian factions - already on increasingly tense terms with the Nazis. Certainly, there was little evidence that suggested the Nazis could be persuaded to reason in regard to their aggression and flagrant anti-Semitism.

Issued on the 31st May 1934, the Barmen Declaration called for the German Church to resist Hitler.

Pastor Paul Schneider - his defiance towards the Nazis would ultimately cost him his life.

So probably conscious of the vulnerability of their own followers – the Christian churches may have felt that discretion was the better part of valour when it came to dealing with the increasingly powerful Nazi party in Germany.

However, religious individuals continued to show bravery throughout the Second World War.

For example, a parson paid a Jewish cancer patient's medical bills and was sentenced to a large fine and several months in prison in 1941, Reformed Church pastor Paul Schneider placed a Nazi sympathiser under church discipline, and he was subsequently sent to Buchenwald, where he was murdered.

In 1945, a Catholic nun was sentenced to death for assisting Jews. In 1943, a Protestant parson spoke out and was sent to Dachau concentration camp, where he died after only a few days.

Not all Christians were so benevolent in their views towards the Jews though. Martin Sasse, a Nazi Party member and bishop of the Evangelical Lutheran Church in Thuringia, as well as a leading member of the Nazi German Christians, published a compendium of Martin Luther's writings shortly after Kristallnacht. (According to Diarmaid MacCulloch, Luther's 1543 pamphlet On the Jews and Their Lies served as a "blueprint" for Kristallnacht.)

Sasse himself "applauded the burning of the synagogues" and the coincidence of the day, writing in the introduction, "On 10 November 1938, on Luther's birthday, the synagogues are burning in Germany." He urged the German people to pay attention to the words "of the greatest anti-Semite of his time, the warner of his people against the Jews.".

International reaction

Kristallnacht sparked worldwide outrage. "A line had been crossed: Germany had left the community of civilised nations," according to Volker Ullrich. It discredited pro-Nazi movements in Europe and North America, causing their popularity to plummet. Many newspapers condemned Kristallnacht, likening it to the murderous pogroms instigated by Imperial Russia in the 1880s.

In protest, the United States recalled its ambassador (but did not break diplomatic relations with Germany), while other governments severed diplomatic relations with Germany. The Kindertransport programme for refugee children was approved by the British government.

Children from a Kindertransport after their arrival in Waterloo Station in London, February 2, 1939. The Kindertransport (German for "children's transport") was an organised rescue effort of children (but not their parents) from Nazi-controlled territory that occurred nine months before the outbreak of World War II. Nearly 10,000 Jewish children were taken in by the United Kingdom from Germany, Austria, Czechoslovakia, Poland, and the Free City of Danzig.

Kindertransport Exhibit Highlights Family Separation in 1930s - Leo Baeck Institute (lbi.org)

William Cooper (1861 - 1941), Australian Aboriginal leader who led a protest to the German consulate in Melbourne, Australia after Kristallnacht.

Public domain

Kristallnacht was a watershed moment in Nazi Germany's relations with the rest of the world.

The brutality of the pogrom, as well as the Nazi government's deliberate policy of encouraging the violence once it had begun, exposed Germany's repressive nature and widespread anti-Semitism.

As a result, global opinion turned sharply against the Nazi regime, with some politicians calling for war.

On 6 December 1938, William Cooper, an Aboriginal Australian, led a delegation of the Australian Aboriginal League on a march through Melbourne to the German Consulate to deliver a petition which condemned the "cruel persecution of the Jewish people by the Nazi government of Germany". German officials refused to accept the document that was offered.

The influence of Goebbels

Propaganda Minister Joseph Goebbels played a major role in causing Kristallnacht and it was possible that he was motivated, not just by his rabid antisemitism, but also by personal reasons to.

Goebbels had recently been humiliated for the ineffectiveness of his propaganda campaign during the Sudeten crisis, suffering a dent to his reputation.

Furthermore, he was also embroiled in a scandal involving a Czech actress, Lda Baarová.

With all this negative publicity and attention, Goebbels needed an opportunity to improve his standing in Hitler's eyes – an event which would both distract people and bolster his own reputation in the eyes of Hitler.

It was on his command that the pogrom started and once the damage had been done – shops smashed, synagogues burnt and jews carted off the concentration camps - he was quick to put his own ‘spin’ on the events.

Joseph Goebbels, German Minister of Propaganda.

Marina Amaral

Brazil artist brings 150 years of history to life in glorious colour | Daily Mail Online

Goebbels, with Hitler and other high ranking Nazi officials, justifying Kristallnacht at a press conference in 1938.

Time magazine

Goebbels attributed the events of Kristallnacht to the German people's "healthy instincts" in an article published on the evening of November 11th. He went on to say: "The German people are anti-Semitic. It has no desire to have its rights restricted or to be provoked in the future by parasites of the Jewish race."

In an interview with the foreign press on the 11th November, Goebbels claimed that the burning of synagogues and damage to Jewish-owned property were "…spontaneous manifestations of indignation against the murder of Herr Vom Rath by the young Jew…"

Timeline of events

9th November 1938:

- 1:15 PM - Ernst vom Rath, a German official, is shot by Herschel Grynszpan, a young Jewish man, in Paris.

- 7:00 PM - News of vom Rath's death reaches the German government.

- 7:30 PM - Propaganda Minister Joseph Goebbels delivers a speech in which he calls for a nationwide attack against the Jewish community in response to vom Rath's death.

- 8:00 PM - Synagogues and Jewish-owned businesses throughout Germany begin to be vandalized and destroyed by organized mobs of Nazi Party members and sympathizers.

Jewish women in Linz, Austria are exhibited in public with a cardboard sign stating 'I have been excluded from the national community (Volksgemeinschaft)', in November 1938.

Galerie Bilderwelt/Getty Images

Photos of Kristallnacht, the 'Night of Broken Glass,' on Its 81st Anniversary (insider.com)

10th November 1938:

- 1:00 AM - The violence and destruction continues throughout the night, with over 1,000 synagogues burned and thousands of Jewish homes and businesses vandalized.

- 6:00 AM - The police and military are finally called in to restore order, but many Jewish families have already been arrested and sent to concentration camps.

Throughout the day - The aftermath of the pogrom is documented, with estimates putting the number of synagogues destroyed at over 1,000 and the number of Jews arrested at approximately 30,000. The event becomes known as "Kristallnacht," or the "Night of Broken Glass," due to the widespread destruction of Jewish-owned storefronts and homes.

Assessment

The results of Kristallnacht were devastating for the German and Austrian Jewish communities. Over 1,000 synagogues were destroyed, and an estimated 30,000 Jews were arrested and sent to concentration camps.

The event also marked a significant escalation in the persecution of Jews, as it was the first time that the Nazi regime had carried out a widespread attack against the Jewish community. This event sent shockwaves throughout the Jewish community and led many to begin the process of emigrating from Germany.

In addition to the immediate effects of Kristallnacht, the event had far-reaching consequences for the future of the Holocaust. It marked a turning point in the Nazi regime's persecution of Jews and set the stage for the systematic extermination of six million Jews during World War II.

The events of Kristallnacht also had a significant impact on the international community, serving as a wake-up call for many to the dangers of the Nazi regime and its intentions towards Jews and other minority groups.

Discovery

Yaron Svoray, an investigative journalist, uncovered a dumpsite in October 2008. The four-football-field-sized site housed an extensive collection of personal and ceremonial items looted during Kristallnacht against Jewish property and places of worship on the night of November 9, 1938.

It is believed that the goods were brought by rail to the village's outskirts and dumped on designated land. Among the items discovered were glass bottles engraved with the Star of David, mezuzot, painted window sills, and the armrests of synagogue chairs, as well as an ornamental swastika.

What happened to Herschel?

Grynszpan was arrested immediately following Vom Rath's shooting and deported to Germany following the invasion of France for questioning by the Gestapo, the Nazi secret state police.

He was transferred from a Berlin detention centre to the Sachsenhausen concentration camp near Berlin, and the last official confirmation of his existence is from September 1942, when many historians believe he was murdered by the Nazis.

Except for eyewitness accounts claiming to have seen him alive in the final weeks of the war and rumours from the late 1950s onwards that he might be living in Paris, Hamburg, or Israel, there has never been any evidence that Grynszpan survived the war. It was widely assumed that he died while being held by the Nazis.

The booking photo of Herschel Grynszpan taken after he was arrested for killing German diplomat Ernst vom Rath in Paris on the 7th November 1938, which set off the Nazis’ Kristallnacht pogrom against Germany’s Jews several days later.

Herschel Grynszpan And The Assassination That Instigated The Holocaust (allthatsinteresting.com)

However, archivists at Vienna's Jewish Museum are certain the newly discovered photograph depicts Grynszpan. A face recognition test on the photograph, taken on 3 July 1946 in a DP (displaced persons) camp in Bamberg, southern Germany, yielded a 95% likelihood - the highest possible match.

Grynszpan appears to be taking part in a demonstration of Holocaust survivors protesting British authorities' refusal to allow them to emigrate to Palestine in the photograph. Armed US army military police standing on a lorry are protecting the demonstrators.

Various claims have been made over the years by people claiming to know where Grynszpan was - that he had changed his name and started a family, that he ran a petrol station outside of Paris, or that he worked in the import-export business.

The alleged photograph of Herschel Grynszpan in 1946.

Vienna Jewish Museum

However, no proof has ever been provided. A German journalist told a court in the early 1960s that Grynszpan was willing to return to Germany and tell the truth about what had happened in exchange for immunity from prosecution. Prosecutors, however, ruled out such a possibility because Grynszpan was a murder suspect who would have to face a murder trial.

Interestingly, Grynszpan never had his day in court back in 1938. Joseph Goebbels was keen to organise a massive show trial in which he could be tried on behalf of all Jews against whom the Nazi regime declared war.

However, Hitler himself cancelled the proceedings after Grynszpan changed his confession to claim the shooting was a so-called crime of passion stemming from his relationship with Vom Rath. It is claimed that whilst in prison, Grynszpan intended to claim that he and vom Rath were secret lovers – something which would cause enormous embarrassment to the Nazis, given their views on homosexuality.

The passage of time and lack of conclusive evidence, either way, continues to present this intriguing, unanswered question. On the one hand, it was rare for Nazis to let their perceived enemies slip through the net – especially when they already had their hands on them. On the other, it seems odd that with the Nazi’s penchant for documenting their various misdeeds and atrocities and love for efficient administration (However grisly the subject), they somehow forgot to record Grynszpan’s fate.

Add to the mix, the general chaos of six years of war – where countless individuals simply disappeared, then it seems likely that the ultimate fate of Grynszpan may forever remain a mystery.

Further reading

Sources:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kristallnacht

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Herschel_Grynszpan

https://facingtoday.facinghistory.org/reflecting-on-kristallnacht-78-years-later

https://www.scuolaememoria.it/site/it/2020/09/15/le-leggi-di-norimberga/?rit=lettura-contenuto

https://www.vintag.es/2014/10/amazing-black-and-white-photographs-of.html

https://www.yadvashem.org/yv/en/exhibitions/communities/wurzburg/during_holocaust.asp

https://i.imgur.com/y60XHmL.jpg

https://hrexach.wordpress.com/2013/11/11/kristallnacht-horror-night-of-november-9-1938/

https://www.history.com/news/kristallnacht-photos-pogrom-1938-hitler

https://www.history.com/news/kristallnacht-started-when-this-diplomat-was-murdered-in-cold-blood

https://encyclopedia.ushmm.org/content/en/photo/jewish-quarter-of-paris-before-world-war-ii

https://fineartamerica.com/art/history

https://www.yadvashem.org/education/educational-materials/ceremonies/kristallnacht.html

https://www.lbi.org/news/kindertransport-exhibition-highlight-family-separation-1930s/

https://jewinthepew.org/2016/05/30/31-may-1934-barth-publishes-barmen-declaration-otdimjh/

https://www.insider.com/kristallnacht-night-of-broken-glass-anniversary-2019-11

Fine Art Images/Heritage Images/Getty Images

Getty Images

Galerie Bilderwelt/Getty Images

Time magazine

Kelly McLaughlin, www.insider.com

https://allthatsinteresting.com/herschel-grynszpan

Morgan Dunn, https://allthatsinteresting.com/