A Missed Opportunity?

The Japanese Second Wave during the attack on Pearl Harbor, launched on the 7th December 1941, is often viewed as a failure or disappointment due to its inability to achieve key strategic objectives.

While the first wave had inflicted significant damage, the Second Wave failed to destroy critical U.S. infrastructure, such as oil reserves, repair docks, and submarine bases, which were essential for the U.S. Navy’s recovery.

...decided against launching a Third Wave...

Most notably, the Second Wave missed the opportunity to target U.S. aircraft carriers, which were absent from the harbor.

These carriers would later play a crucial role in the Pacific War, contributing to Japan's defeat. Additionally, Japan decided against launching a Third Wave, which could have caused more lasting damage to American capabilities.

The failure of the Second Wave to deliver a decisive blow allowed the U.S. Navy to rebound quickly, leading to a swift American resurgence in the Pacific.

Flawed Training

Training for the Val dive-bomber crews ahead of the Pearl Harbor attack was rigorous but also fraught with challenges.

The program involved six weeks of intense flying, often with multiple flights per day. However, it was hindered by the need for long flights to remote bombing ranges, which left the crews fatigued.

Most of the pilots were young and inexperienced, many just 18 to 20 years old, freshly graduated from primary flight school.

Contrary to the common belief that the attack was carried out by seasoned veterans of the China campaigns, the majority of these aviators had limited flight experience, with only a few having significant flight time.

This myth, likely fueled by disbelief that America’s Navy could be devastated by such inexperienced youth, endures to this day.

The Aichi D3A1 99 dive bomber - a mainstay of the Japanese attacking force. The "Val," was a widely used in 1941 and renowned for its speed and agility. It played a crucial role in attacks like Pearl Harbor, delivering precision strikes with its 500 kg bomb load.

...dive-bombing technique unique to the Imperial Japanese Navy...

Much of the six-week training regimen was spent on basic flying skills, carrier qualifications, and formation flying.

Night training was originally planned, as the initial idea was to launch the attack before dawn, but this was later scrapped when the pilots’ night flying abilities were deemed insufficient.

A critical part of their training involved learning the team dive-bombing technique unique to the Imperial Japanese Navy, a method that would later contribute to their shortcomings during the attack.

Japanese Pilots in a more relaxed moment. Japanese pilots training for the Pearl Harbor attack underwent a rigorous six-week program focused on basic flying skills, carrier qualifications, and team dive-bombing techniques. Many were young and inexperienced, often lacking adequate night flying training, which hampered their effectiveness during the chaotic conditions of the actual mission on December 7, 1941.

...some aircraft failed to recover from the steep dives...

The Val pilots attacked in shotai, teams of three aircraft. The leader would dive from 9,843 feet at a 60-degree angle, aiming at the target's foremast.

Bomb release typically occurred at 1,968 feet, but for Pearl Harbor, Lieutenant Commander Takashige Egusa, head of dive-bomber training, reduced the release altitude to 1,312 feet for greater accuracy.

Despite this adjustment, lives were lost during training when some aircraft failed to recover from the steep dives.

Though their method averaged a 55 percent hit rate in practice, the complexities of real combat would prove far more difficult.

The Target Revealed

Excitement mixed with anxiety as the Japanese pilots prepared for their mission: attacking the American fleet in Pearl Harbor.

The gravity of their task was clear. They were told that the fate of the Japanese nation rested on their shoulders.

For the young men of the second wave, it was especially daunting—they would arrive about one hour after the American defenses had been fully alerted.

They knew many of them would not survive the day. But survival wasn’t their focus; their mission was. Their entire existence in that moment was dedicated to the single bomb they carried into battle.

...insufficient to seriously damage a battleship...

Their primary target was U.S. aircraft carriers. Even if the carriers had already been sunk or capsized by the first wave, their orders were to ensure they were completely obliterated, made unsalvageable.

This directive came from Commander Minoru Genda, known as “Mad Genda,” who believed that battleships were obsolete in modern warfare.

In Genda’s eyes, the real prize was the U.S. aircraft carriers, and they needed to be utterly destroyed.

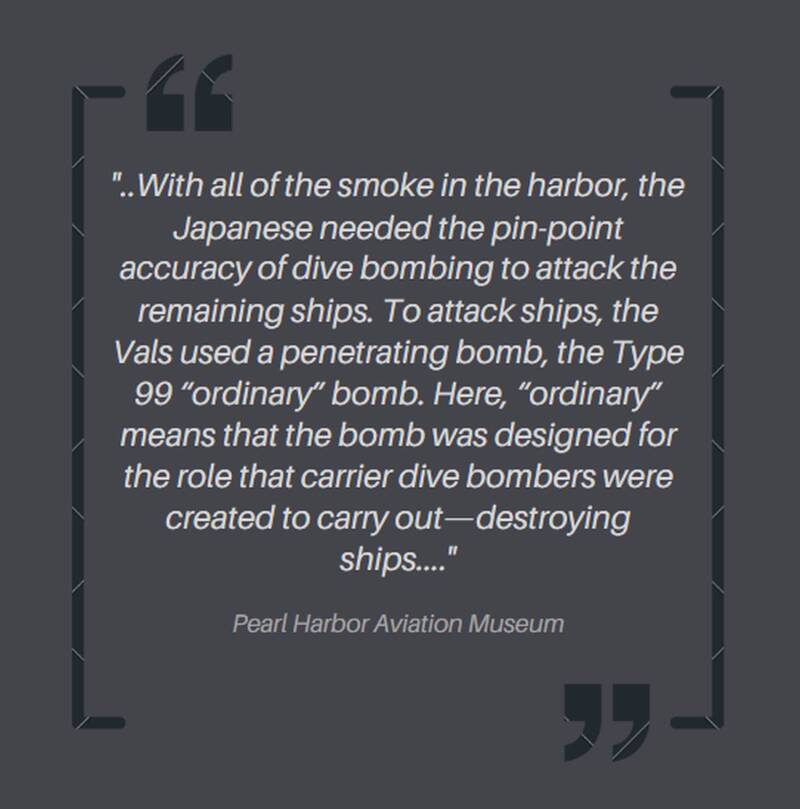

Once the carriers were demolished, the pilots were to focus on cruisers, avoiding battleships altogether.

This was because the bombers’ Type 99 Number 25 Model 1 bomb, weighing 554 pounds, could only penetrate 2 inches of armor, which was insufficient to seriously damage a battleship.

For the pilots, this was a disappointment, as they believed sinking battleships—the core of American sea power—would be the true measure of aviation’s worth.

...a jumble of contradictions...

However, deep down, the pilots felt conflicted. For this critical battle, none of them wanted to give their lives targeting anything they saw as secondary, like cruisers. Battleships were seen as more prestigious targets, but they had to follow orders.

In mid-November, the carriers departed Japan for Pearl Harbor. Along the way, the pilots were briefed by Commander Mitsuo Fuchida, one of the attack’s primary planners. Fuchida would lead the first wave from a Kate bomber, carrying an armor-piercing bomb made from a repurposed battleship shell.

His briefings, however, were a jumble of contradictions. The bombers were told to concentrate their attacks but not overconcentrate. They were to strike nearly simultaneously but follow a complex prioritization of targets.

...to trap the Pacific Fleet...

The goal was to sink ships, not just damage them. Additionally, they were instructed to avoid hitting ships that were already sunk—except for carriers, which should be attacked regardless of their status, even if capsized.

The pilots were also warned to sink any battleship under way in the harbor channel to trap the Pacific Fleet, though their bombs were ineffective against battleships.

As the pilots studied the charts and examined a detailed plaster model of Pearl Harbor, they must have been overwhelmed by these conflicting instructions.

There was little clarity on how to differentiate a capsized carrier from a battleship, and some may have even noticed that the channel was too wide to be fully blocked by a sunken ship.

...the Americans would have less time to bolster their defences...

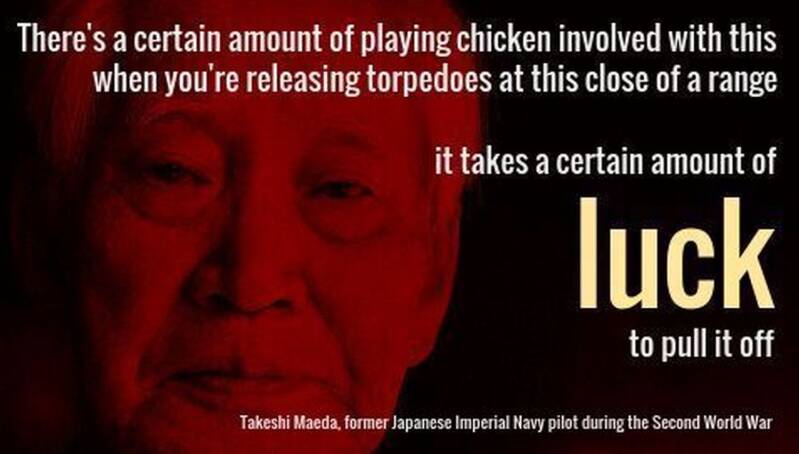

After the first wave departed, the Val dive-bombers were brought up from the hangars.

Despite the ship’s pitching decks and harsh spray, the flight deck crews managed to prepare the aircraft for takeoff 15 minutes ahead of schedule—an important accomplishment, as it meant the Americans would have less time to bolster their defences.

The Vals launched and formed up with the Kates and Zeros. As they approached Oahu, the formation broke apart to pursue their separate missions.

The Zeros and Kates targeted the airfields, while the Vals descended from cruising altitude to 9,843 feet, preparing to attack the harbor.

The chotai (groups of three shotai) leaders gave hand signals to release the bombs, and each leader selected a target.

The attack was meant to last a brief, frenzied five minutes. But reality would prove far more complicated.

Battling the weather & radios

To their dismay, the pilots of the second wave saw a solid cloud deck looming 4,922 feet below them. Diving through it was not an option—its thickness was unknown, and they had no idea where the targets or even the harbor were. Worse, they feared that Oahu’s mountains could be concealed beneath the clouds, adding another layer of danger.

The weather forecast had warned of a front arriving, bringing clouds between 3,500 and 5,000 feet, but the young aviators were neither prepared nor trained for this situation.

They desperately needed guidance from their experienced leaders. Perhaps Commander Fuchida, who was orbiting the harbor below, knew how thick the clouds were.

Maybe one of their planes had already penetrated the cloud cover and could report back, or their experienced chotai (flight leader) had some advice.

...the rushed installation process had been poorly coordinated...

However, if any pilot had put on his voice radio headset, hoping for instructions, all he would have heard was static.

A few months before the Pearl Harbor attack, the Imperial Japanese Navy had retrofitted their aircraft with voice radios.

Unfortunately, the rushed installation process had been poorly coordinated between the technicians and the airframe manufacturers.

The technicians were paid based on how many radios they installed, with little to no quality control. As a result, many radios were hastily and improperly fitted into the aircraft, often mounted on bungee cords as a makeshift shock absorber.

...periodically discharging in loud bursts of static through the radios...

The poorly installed radios were often unusable. Their controls were obscured or out of reach, and excess wiring was looped haphazardly inside the plane, creating makeshift antennas that picked up interference from the engine’s spark plugs.

This caused a constant roar in the pilots’ headphones. Worse, static electricity would build up in the aircraft fuselage during flight, periodically discharging in loud bursts of static through the radios.

In frustration, some pilots eventually removed the radios altogether, considering them useless and a drag on the aircraft’s performance.

On the 7th December 1941, voice radios were ineffective, leaving each shotai leader to choose his target independently, without command-and-control communication.

A Scattergun Approach

The Vals’ formation quickly broke apart as individual shotai (flight team) leaders frantically searched for gaps in the thick cloud cover.

With no centralized control or coordination, and no functional voice radios to guide them, communication among the pilots was impossible.

Whenever a shotai leader found a clearing in the clouds, he would accelerate toward it and dive or spiral down, but this often resulted in the separation of his team.

Once isolated, each pilot had to independently navigate through the clouds, searching for a way to reach their targets below.

...identifying targets was a major challenge...

Beneath the cloud cover, the Vals encountered intense anti-aircraft (AA) fire, far surpassing anything even the veterans of the China wars had experienced.

For the young, inexperienced pilots, it was terrifying. Amidst the chaos, identifying targets was a major challenge.

Thick smoke and shaded awnings obscured the ships’ outlines, making it difficult to distinguish battleships from auxiliary vessels.

The overwhelming columns of smoke further clouded their vision.

...rendering their bombsights useless...

The low-hanging clouds also made the Japanese pilots’ standard dive-bombing technique impossible.

Normally, they would begin their 60-degree dives from around 3,280 feet, lining up targets precisely with their bombsights.

But now, without sufficient altitude and visibility, they resorted to 20- to 40-degree glides, rendering their bombsights useless.

For the first time, the pilots had to rely on instinct, bombing "by eye."

Some were seen initiating attacks on one ship, only to divert mid-dive to another target in the confusion.

...the crew ordered the forward magazine flooded to prevent an explosion...

Through a break in the clouds, pilots spotted the battleship USS Nevada (BB-36) moving in the channel.

Ace dive-bomber Lieutenant Commander Takashige Egusa led elements of two shotai down in an attack. Fourteen Vals targeted the Nevada, scoring five bomb hits—their most accurate strike of the battle.

Fires ignited on the ship, and the crew ordered the forward magazine flooded to prevent an explosion.

However, a critical misunderstanding led to the after magazine also being flooded, which caused the ship to settle deeper in the water.

...internal flooding worsened as water poured through ill-fitting doors...

The Nevada, commissioned in 1916 and nearing the end of its service life, was already in poor condition.

Damage from a previous torpedo hit had compromised its watertight integrity, and the ship’s internal flooding worsened as water poured through ill-fitting doors, leaking pipes, and damaged decks.

Eventually, the battleship was beached to prevent sinking in the channel—more a victim of poor maintenance and internal failures than the bomb damage itself.

Japanese Bombs and Torpedos at Pearl Harbor

| Weapon | Weight | First Wave | Second Wave |

|---|---|---|---|

| Type 99 Model 5 ordinary (anti-ship) bomb | 800 kg/1,763 lb | B5N2 Kates | |

| Type 99 Model 1 ordinary (anti-ship) bomb | 250 kg/551 lb | D3A1 Val | |

| Type 98 land bomb | 250 kg/551 lb | D3A1 Val | B5N2 Kates |

| Type 97 land bomb | 60 kg/132 lb | B5N2 Kates | |

| Type 91, Model 2 Torpedo | 838 kg/1,847 lb | B5N2 Kate | |

| Type 91, Model 2 Torpedo | 205 kg/452 lb warhead | B5N2 Kate |

Non-Priority Targets

The Vals' attack on Pearl Harbor stretched over 40 minutes as the remaining 60 or more bombers struggled to find gaps in the heavy cloud cover.

Anti-aircraft (AA) fire was able to concentrate on individual planes as they emerged from the clouds in small groups.

The disjointed attack led to 14 Vals being shot down and another 14 returning to their carriers so damaged that they were later written off.

...attacks occurring while the ships were still in the harbor...

With attacks scattered across the harbor, many pilots became disoriented.

Some even mistook the moorings northwest of Ford Island—where auxiliary ships like the tenders USS Curtiss (AV-4), Tangier (AV-8), and Dobbin (AD-3) were stationed—for Battleship Row.

As a result, 16 Vals attacked auxiliary ships instead of their intended targets.

Seven Vals attempted to strike the destroyers USS Helm (DD-388) and Dale (DD-353), with two attacks occurring while the ships were still in the harbor and five after they had moved out to sea.

However, these attacks resulted in only two near-misses that caused no serious damage to the destroyers.

The USS Helm was repeated targeted during the attack on Pearl Harbor. Targeting the Helm during the Pearl Harbor attack was a mistake because it was a smaller, less significant destroyer, not a primary target like battleships or aircraft carriers. The effort diverted resources from hitting more strategically valuable vessels, limiting the overall impact of the attack.

https://hamptonroadsnavalmuseum.blogspot.com/2015/06/uss-helm-dd-388-for-duration.html

...a pilot's honor was tied to success...

Of the 78 Vals deployed in the attack, only 17 targeted cruisers, which were among their priority targets and vulnerable to their bombs.

If the USS Nevada (BB-36) is considered part of their mission, that number rises to 31.

Still, fewer than half of the dive-bombers attacked their assigned targets. Japanese aviators claimed a total of 49 hits, but in reality, only 15 bombs found their mark.

Overclaiming was common in aerial combat, but it was particularly pronounced in the Japanese Navy, where a pilot's honor was tied to success.

Fallen pilots were always credited with a hit, whether accurate or not.

...may have been mistaken for a larger vessel...

Thirty-three hits were claimed against battleships and 16 against cruisers, but there was only one confirmed hit on a cruiser.

Destroyers received six hits, including three on the USS Shaw (DD-373), which was in a floating dry dock and may have been mistaken for a larger vessel like a cruiser or battleship.

Bombs that struck the destroyers Cassin (DD-372) and Downes (DD-375) were actually aimed at the battleship USS Pennsylvania (BB-38), which shared their dry dock.

The USS Shaw after bombs penetrated its forward magazine. The sinking of the Shaw during the second wave at Pearl Harbor was significant due to the dramatic explosion of its forward magazine, captured in iconic images. However, compared to larger battleships like the Arizona, Shaw's destruction had less strategic impact on U.S. naval capabilities.

https://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-5155311/Full-horror-Pearl-Harbor-brought-life-color.html

Royston Leonard Mediadrumworld.com

...debate over carriers versus battleships was still ongoing in the Japanese Navy...

Overall, only 10 percent of the bombs hit their intended targets, far below the expected 60 percent.

After the battle, Commander Mitsuo Fuchida, who had observed the attack from the air, compiled a report for Emperor Hirohito.

Remarkably, the number of hits he reported matched exactly with his pre-battle predictions. Fuchida likely had multiple reasons for this.

First, he was close friends with some of the dive-bomber pilots, including the renowned Egusa, and wanted to protect their reputations.

Second, he sought to emphasize the effectiveness of carrier-based aviation, as the debate over carriers versus battleships was still ongoing in the Japanese Navy.

Finally, as one of the main planners of the attack, Fuchida had a vested interest in proving that his strategy was sound and his predictions were accurate.

A Shift to Battleships?

After the war, a curious mystery surfaced regarding the instructions given to Japanese aircrews before the second wave of the Pearl Harbor attack.

Some aviators claimed that they were informed just prior to launch that an intelligence agent had reported “no carriers in Pearl Harbor.”

With no carriers to strike, one pilot stated they were told to attack the same targets as the first wave, specifically the battleships. Another aviator mentioned that they were instructed to “finish off ships damaged in the first attack, preferably the battleships.”

...both believed that battleships were an ineffective use of ammunition...

However, this narrative raises doubts. While there was an intelligence report received the previous day, it was dismissed by key planners Commander Minoru Genda and Mitsuo Fuchida.

If such a report had been credible, why wait until the aircraft were on the flight deck to inform the pilots?

Furthermore, any changes in target assignments would have had to come from Genda or Fuchida, the only individuals with the authority to make such decisions, yet both believed that battleships were an ineffective use of ammunition.

....believing their lives were on the line...

The questionable story might serve several purposes. After the raid, Fuchida prepared a report boasting inflated numbers of successful hits by Japanese aircraft.

In reality, only 17 out of the 78 Vals attacked their designated targets, achieving far fewer hits than claimed.

Would Japanese warriors, believing their lives were on the line and facing a 50 percent chance of not returning, be satisfied with attacking only secondary targets?

The absence of effective radio command-and-control allowed individual shotai leaders to act independently.

Most opted to engage battleships or what they perceived to be battleships.

...a collective, passive-aggressive rebellion among the pilots...

These alleged last-minute instructions could have been a post-facto justification for the pilots' actions.

Alternatively, a pilot might have invented a fictitious order to rationalize their choices or circulate it among peers.

It is also possible that there was a collective, passive-aggressive rebellion among the pilots, leading them to pursue battleships regardless of official guidance. Ultimately, the answer remains buried in history.

The lack of strong radio communication and control from experienced leadership allowed the shotai leaders to pursue their own agendas, resulting in many returning to Japan with the dubious satisfaction of having struck a battleship, a significant symbol of American naval power.

This situation only added to the confusion surrounding the operation and the decisions made during the attack.

The Cruisers Escape

With no aircraft carriers available, the second-wave dive bombers should have focused their attacks on the eight cruisers in port.

A well-executed strike with three or four Type 99 bombs could sink a cruiser, providing enough firepower to potentially cripple all eight vessels.

This strategic targeting was crucial, as these cruisers would later become integral to the carrier task forces and play significant roles in the surface battles around Guadalcanal.

...severely hampered the second wave’s effectiveness...

However, the planning staff failed to consider the likelihood of poor weather conditions typical of Hawaii.

The pilots were not trained to conduct bombing runs in anything but ideal weather, which severely hampered the second wave’s effectiveness.

The Vals' desire to target battleships further undermined the operation, resulting in minimal damage to these vessels while leaving the cruisers largely unscathed.

...a significant disparity between reported and actual attacks...

Except for Lieutenant Commander Egusa’s attack on the USS Nevada, there was a complete lack of command-and-control during the second wave.

Pilots operated independently, leading to a chaotic engagement marked by a significant disparity between reported and actual attacks.

This confusion stemmed from the disorientation pilots experienced when they emerged from the clouds, compounded by the intense anti-aircraft (AA) fire they faced.

Effective voice-radio communication could have enabled the formations to remain together, descending through the same gaps in the clouds. Laggard pilots could have been informed of the cloud deck’s altitude, allowing for safer descent.

Leaders could have exerted control over target selection, coordinating attacks to overwhelm AA defenses. Had the aircraft appeared simultaneously, the AA fire would have been less concentrated, resulting in more effective strikes against the cruisers.

...she was back in action just eighteen months later...

Unfortunately, the planners overlooked the use of voice radio in their strategy, a decision influenced by a combination of the individualistic bushido spirit and the poor installation of radio equipment.

Ultimately, none of the hits delivered by the Vals were of strategic significance.

Their purported success against the Nevada proved to be an illusion, as she was back in action just eighteen months later, shelling Imperial Japanese Army positions in the Aleutians.

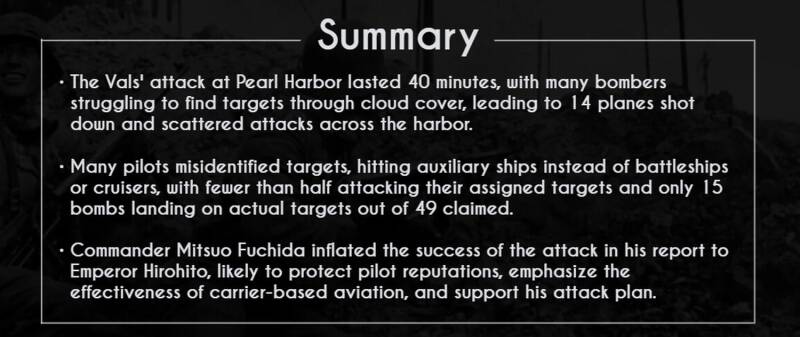

Missing the Oil

The failure of the Japanese forces to target the oil facilities at Pearl Harbor during the second wave of the attack, stands out as a significant missed opportunity.

At that time, the naval base held vital fuel reserves essential for the U.S. Pacific Fleet's operational capabilities.

If the Japanese had successfully targeted these facilities, they could have severely hampered American naval operations in the Pacific, delaying any counteroffensive.

Pearl Harbor, Oahu, Hawaii - Aerial view of the Submarine Base, with part of the fuel farm in the foreground, looking southwest on 13 October 1941. Note the artfully camouflaged fuel tank in center, painted to resemble a building. Also camouflaged as a building is the most distant fuel tank in the upper left. The tank farms at Pearl Harbor held crucial fuel reserves for the U.S. Pacific Fleet. The Japanese failure to target these storage facilities during the attack allowed the U.S. Navy to recover quickly, as fuel supply was essential for naval operations and sustaining America's war efforts in the Pacific.

...critical to sustaining the fleet's operations...

During the planning stages, Japanese planners, including Commander Minoru Genda, focused heavily on destroying battleships and aircraft carriers, viewing them as the key to American naval power.

This narrow focus overshadowed the importance of oil facilities, which were critical to sustaining the fleet's operations.

Although the first wave of the attack inflicted significant damage on battleships and aircraft, the second wave failed to capitalize on the chaos created earlier in the day.

...vital installations such as the oil storage tanks were overlooked...

The pilots of the second wave were disoriented and uncoordinated, lacking effective command and control.

This disorganization meant that many bombers did not effectively identify or prioritize their targets.

As a result, vital installations such as the oil storage tanks were overlooked in favour of less strategically significant ships.

The Japanese dive bombers concentrated their efforts on other vessels, resulting in only superficial damage.

...a reliance on distant supply lines...

Moreover, the intense anti-aircraft fire they encountered further compounded the pilots’ inability to carry out effective strikes.

Had they targeted the oil reserves, the U.S. Navy would have faced a more challenging logistical situation, forcing a reliance on distant supply lines and delaying their recovery and response capabilities in the Pacific theater.

In hindsight, the decision to ignore these critical resources during the second wave underscored a strategic oversight that would ultimately hinder Japanese efforts in the prolonged conflict that followed.

Conclusion

Is it fair to consider the Second Wave a failure or disappointment? It aimed at finishing the destruction of U.S. naval and air forces, did not achieve its full objectives.

While the initial wave inflicted heavy damage, the Second Wave failed to locate and destroy key U.S. assets, most notably the aircraft carriers that were absent from the harbor.

Furthermore, important infrastructure like fuel storage, repair yards, and submarine bases remained untouched, allowing the U.S. Navy to recover relatively quickly.

The decision not to launch a Third Wave attack, which could have caused more lasting damage, is seen by some historians as a missed opportunity.

This miscalculation contributed to the U.S.'s rapid resurgence and decisive victories later in the Pacific War, marking the Second Wave as strategically incomplete.

...could be considered to have been neutralized to some degree...

However, the Second Wave did further weaken the U.S. Pacific Fleet, sinking additional battleships and disabling aircraft. Japan’s immediate goal of neutralizing American naval power in the Pacific was partially achieved, allowing Japan to expand across Southeast Asia and the Pacific without significant American resistance for several months.

The Second Wave reinforced Japan’s tactical success on that day, ensuring that the U.S. Navy would remain ineffective in the early phase of the Pacific War, delaying American counteroffensives. Despite its limitations, the Second Wave contributed to Japan's short-term military successes.

On balance though, through flawed planning, poor equipment, and the intervention of the god of weather, the second-wave dive-bomber attack on 7 December 1941 could be considered to have been neutralized to some degree.

Pearl Harbor was a tactical disaster for the U.S. Navy – a serious one —but it could have been worse.