The Poles rise up

The Warsaw Uprising was a military campaign that took place in Warsaw, Poland during the Second World War.

On 1st August 1944, the Polish resistance movement, known as the Home Army, launched a rebellion against the Nazi occupation of the city.

The uprising was sparked by the approach of the Soviet Red Army, which was advancing on the eastern front and had reached the outskirts of Warsaw.

The Home Army hoped to liberate the city before the Soviets arrived, in order to establish a Polish provisional government, free from the malignant influence of Stalin.

The areas of Warsaw controlled by the Home Army on August 4, 1944. Not all areas outside of the designated zones were controlled by the Germans, since there were no stable front-lines and in early August much of the city was still a no-man’s land.

The uprising was a desperate and ultimately unsuccessful attempt to drive out the German forces that had occupied Warsaw for five years. The resistance fighters faced overwhelming odds, as they were poorly equipped and outnumbered by the Germans. Despite their bravery and determination, they were unable to break the Nazi grip on the city. After 63 days of fighting, the uprising was crushed, and the remaining resistance fighters were either killed or captured.

The Warsaw Uprising is remembered as a tragic and heroic event in Polish history. It is a symbol of the suffering and sacrifice of the Polish people during World War II and of their resistance to the Nazi occupation.

A Polish fighter during the uprising.

Mikołaj Kaczmarek/Warsaw Rising Museum

Prelude

The Polish people suffered appallingly under German rule. Between 1939 and 1945, approximately 6 million Polish citizens—nearly 21.4% of Poland's population—died as a result of the occupation, half of whom were ethnic Poles and the other half of whom were Polish Jews.

Over 90% of the deaths were non-military in nature, as the majority of civilians were deliberately targeted in various actions launched by the Germans and Soviets.

During the German occupation of pre-war Polish territory, 1939-1945, the Germans murdered 5,470,000-5,670,000 Poles, including 3,000,000 Jews, in what the Nuremberg Trials described as a deliberate and systematic genocide.

Warsaw Ghetto, Nazi-occupied Poland, 1940. The signs read, "Typhus area. Passage permitted only while traveling."

By early July 1944, Soviet forces had repulsed German formations across a wide front stretching from Lithuania in the north to the Black Sea in the south. On 13th July, Vilnius surrendered to the Russians, and the main Soviet spearhead moved towards the Vistula River.

Brest-Litovsk and Lvov fell to the Soviets over the next two weeks, and the Red Army then swung north towards Warsaw. By the 1st of August, Soviet troops had entered the Praga suburb east of the Vistula River.

In their rush to Warsaw, the Soviets had neglected intelligence gathering, flank protection, and over-extended their supply lines to the point where a well-planned and timely attack launched by General Walter Model stopped the Red Army's advance just short of Warsaw, preventing them from crossing the Vistula - this after Hitler had finally agreed to release four experienced and fresh panzer divisions to Model.

This would have a crucial effect on the outcome of the Uprising itself. The German actions forced the Soviets to pause in order to regroup, which gave the German Army Group Centre the time and space it needed to deal with eliminating resistance in Warsaw.

General Walter Model. His timely and effective attack on the Russian forces would buy time for the German forces to suppress the Warsaw Uprising.

Third Reich Color Pictures: Generalfeldmarschall Walter Model

The Eastern Front during Operation Bagration: 22 June — 19 August 1944. By the start of August, the front line had crept to within a few kilometres of Warsaw.

There were several factors that contributed to the decision to launch the Warsaw Uprising.

- One of the main factors was the approach of the Soviet Red Army on the eastern front. In the summer of 1944, the Soviets had reached the outskirts of Warsaw and were making rapid progress against the Germans. The Polish resistance movement, known as the Home Army, saw this as an opportunity to drive the Germans out of the city and establish a Polish provisional government before the Soviets arrived.

- Another factor was the deteriorating situation in Warsaw itself. The city had been occupied by the Germans for five years, and the population was suffering from widespread hunger, disease, and oppression. Many people saw the uprising as a chance to break free from Nazi rule and reclaim their city.

- Finally, the Allied powers, particularly the United Kingdom, had promised support for the uprising. This included airdrops of weapons and supplies, as well as political support.

"KAŻDY POCISK JEDEN NIEMIEC" (One German for every bullet....)

Stanisław Mikołajczyk, Prime Minister of the Polish government-in-exile (14th July 1943 – 24th November 1944).

Getty Images

The Warsaw Uprising, or some form of insurgency in Poland, had been planned for a long time. Warsaw was chosen in part due to its status as a pre-war capital. The allies anticipated that the Germans would want to keep Warsaw as a tool of morale, communications, supply, and troop movement for as long as possible.

The Polish government-in-exile was eager for support from the other allies. As a result, they made frantic diplomatic efforts to gain the support of their allies prior to the start of the battle. Although supply drops were made by American, British, and Polish forces prior to and during the Uprising, the majority of them ended up in German hands. As a result, the Polish Home Army forces were severely undersupplied.

Soviet T-34 tanks on the streets of Lvov 1944, approximately 250 miles from Warsaw. During the summer of 1944, Russian forces had made rapid advances across the Eastern Front leading the Poles to believe that they could rely on Russian support when the uprising started.

Overall, the decision to launch the Warsaw Uprising was driven by a combination of military, political, and humanitarian considerations. It was a desperate attempt to drive out the Germans and reclaim the city, and ultimately, it was a tragic and heroic event in Polish history.

Armia Krajowa

The Polish Home Army (Armia Krajowa, or AK) was the main Polish resistance movement during World War II.

It was formed in February 1942, after the fall of Poland to the Germans, and was made up of soldiers and civilians who opposed the Nazi occupation.

The Home Army was responsible for organizing and coordinating the resistance efforts of various Polish underground groups, including sabotage, intelligence gathering, and military operations.

The Home Army was affiliated with the Polish government-in-exile, which was based in London, and received support from the Allied powers.

However, it operated largely independently and was responsible for its own funding, weapons, and logistics.

Members of the Home Army in Warsaw during the uprising.

Mikołaj Kaczmarek

The Home Army played a significant role in the Warsaw Uprising. However, despite the bravery and determination of the resistance fighters, the uprising was ultimately unsuccessful, and the Home Army was forced to go underground after it was crushed by the Germans.

After the war, the Home Army was dissolved by the communist government of Poland, and many of its members were arrested and imprisoned. Today, the Polish Home Army is remembered as a symbol of resistance and national pride.

Insurgents, wearing captured German helmets, firing at the Germans.

Mikołaj Kaczmarek/Warsaw Rising Museum

German forces

The Germans declared the town "Festung Warschau" (Fortress Warsaw) by the end of July. It had to be protected at all costs from the Soviet offensive. The July 20 Plot and the failed attempt to assassinate Adolf Hitler, on the other hand, forced many German units to withdraw westward through Warsaw.

The Home Army interpreted it as a sign of German defeat. The number of German soldiers in the area was significantly reduced.

German soldiers shelter in a shop window during the uprising.

On 27th July, the governor of the General Government, Hans Frank, summoned 100,000 Polish men between the ages of 17 and 65 to gather at various locations in Warsaw the following day.

They were to be employed in the construction of Wehrmacht fortifications in and around the city.

The Home Army saw this as an attempt to neutralise the underground forces, and the underground urged Warsaw residents to ignore it. General Tadeusz Bór-Komorowski ordered the full mobilisation of Home Army forces in the Warsaw area, fearing German retaliation.

German units stationed in and around Warsaw were divided into three categories in late July 1944.

The first and most numerous were the Warsaw garrison. It had approximately 11,000 troops under General Rainer Stahel as of 31st July.

For months, these well-equipped German forces prepared to defend the city's key positions.

Several hundred concrete bunkers and barbed wire lines guarded the German-occupied buildings and areas.

Apart from the garrison, there were numerous army units stationed on both banks of the Vistula and throughout the city. The second category was police and SS, led by SS and Police Leader SS-Oberführer Paul Otto Geibel, with an initial strength of 5,710 men, including Schutzpolizei and Waffen-SS.

Various auxiliary units, including detachments of the Bahnschutz (rail guard), Werkschutz (factory guard), and the Polish Volksdeutsche (ethnic Germans in Poland), as well as Soviet former POW of the Sonderdienst and Sonderabteilungen paramilitary units, comprised the third category.

The German side received reinforcements on a daily basis during the uprising. By 20th August, German forces had grown to approximately 25,000 men. Detachments from three panzer divisions - the 25th, the 19th, and the "Hermann Goering" divisions - were drafted into action on a regular basis. Aside from bomber planes, the Germans used numerous sappers, self-propelled "Goliath" mines and exploding tanks used for demolishing fortifications, rocket launchers, and the heaviest artillery (including 600mm "Karl" mortars).

In early August, Stahel was replaced as overall commander by SS-General Erich von dem Bach.

As of August 20, 1944, the German combat units directly involved in the fighting in Warsaw numbered 17,000 men divided into two battle groups:

Well-equipped Waffen SS soldiers during the uprising.

Bundesarchiv. bild 1011-695-0407-26

- Battle Group Rohr (commanded by Major General Rohr), which included 1,700 soldiers from the anti-communist S.S. Sturmbrigade R.O.N.A. Russkaya Osvoboditelnaya Narodnaya Armiya (Russian National Liberation Army, also known as Kaminski Brigade) under German command and made up of Russian, Belorussian, and Ukrainian collaborators, was a German-led operation.

- Attack Group Dirlewanger (commanded by Oskar Dirlewanger), which included Aserbaidschanische Legion (part of the Ostlegionen), Attack Group Reck (commanded by Major Reck), Attack Group Schmidt (commanded by Colonel Schmidt), and various support and backup units made up Battle Group Reinefarth, which was led by SS-Gruppenführer Heinz Reinefarth.

German soldiers setting up Goliath Tacked mines during the Uprising. August, 1944.

German soldiers walking by fires set in the Warsaw Ghetto during the Uprising.

sovfoto/universal images group/REX/Shuttershock Mikołaj Kaczmarek

The Nazi forces included approximately 5,000 regular troops; 4,000 Luftwaffe personnel (1,000 at Okcie airport, 700 at Bielany, 1,000 in Boernerowo, 300 at Suewiec, and 1,000 in anti-air artillery posts throughout the city); and approximately 2,000 men of the Sentry Regiment Warsaw (Wachtregiment Warschau), including four infantry battalions (Patz, Baltz, No. 996, and No. 997).

The German garrison received support of Russian Cossacks in rebellion against the Soviets in Warsaw against the Poles.

20 Facts that Brutally Highlight the Warsaw Uprising of 1944 (historycollection.com)

Objectives

The Uprising began as part of the nationwide Operation Tempest, which was launched during the Soviet Lublin-Brest Offensive.

The main Polish goals were to drive the Germans out of Warsaw while also assisting the Allies in defeating Germany.

Another political goal of the Polish Underground State was to liberate Poland's capital and reestablish Polish sovereignty before the Soviet-backed Polish Committee of National Liberation took control.

Other immediate causes included the threat of mass German round-ups of able-bodied Poles for "evacuation," calls for an uprising from Radio Moscow's Polish Service, and an emotional Polish desire for justice and vengeance against the enemy after five years of German occupation.

Regional organization of Armia Krajowa in 1944.

'W' hour

After days of deliberation, the Polish headquarters set the "W-hour" (from the Polish wybuch, "explosion"), the start of the uprising, for 17:00 the following day. Because the under-equipped resistance forces were prepared and trained for a series of coordinated surprise dawn attacks, the decision was a strategic miscalculation.

Furthermore, despite the fact that many units had already been mobilised and were waiting at assembly points throughout the city, the mobilisation of thousands of young men and women was difficult to conceal. Fighting began in advance of "W-hour," particularly in Oliborz, as well as around Napoleon Square and Dbrowski Square. The Germans had anticipated an uprising, but they had underestimated its size and strength. In response Governor Fischer - realising that a major battle was likely to break out - put the garrison on full alert at 16:30.

Polish insurgents with a captured mortar.

The resistance captured a major German arsenal, the main post office and power station, and the Prudential building that evening. Castle Square, the police district, and the airport, on the other hand, remained in German hands.

It was clear that the first few days would be critical in laying the groundwork for the rest of the battle.

The resistance fighters would be most successful in the districts of City Centre, Old Town, and Wola.

However, several major German strongholds would remain a thorn in the side of the Poles, and they would suffer heavy losses in some areas of Wola, which in turn would force an early retreat.

In other areas, such as Mokotów, the attackers were unable to secure any objectives and only controlled the residential areas.

"W" Hour August 1, 1944. Patrol of Lieutenant Stanisław Jankowski "Agaton" from the "Fist" battalion on Kazimierz Wielki Square on the way to Srodmiescie. From the right, tenement houses: 8, 10 and 12 Kazimierza Wielkiego Square, in the background on the left a building on the Wronia 3 property.

Stefan Bałuk, Warsaw Uprising Museum

Insurgents fighting in the rubble of Warsaw. Note the armbands both men wear which identify them as Polish fighters.

Mikołaj Kaczmarek

Young insurgents manning the trenches during the Uprising.

A large concentration of German forces drove the Poles back into hiding in Praga, on the east bank of the Vistula. Most importantly, insurgents in different areas failed to communicate with one another and with areas outside of Warsaw, isolating each sector from the others.

Following the initial hours of fighting, many units adopted a more defensive strategy, and civilians began erecting barricades.

Despite the difficulties, the majority of the city was in Polish hands by 4th August, though some key strategic points remained unconquered.

The Germans were caught off guard by the sudden rebellion, and their initial response was disorganized. However, they quickly mobilized their forces and began to fight back.

The fighting would be fierce and intense, with both sides suffering heavy casualties. The insurgents suffered over 2000 casualties on that first day. At least 500 Germans were killed or injured, and several hundred Poles taken prisoner.

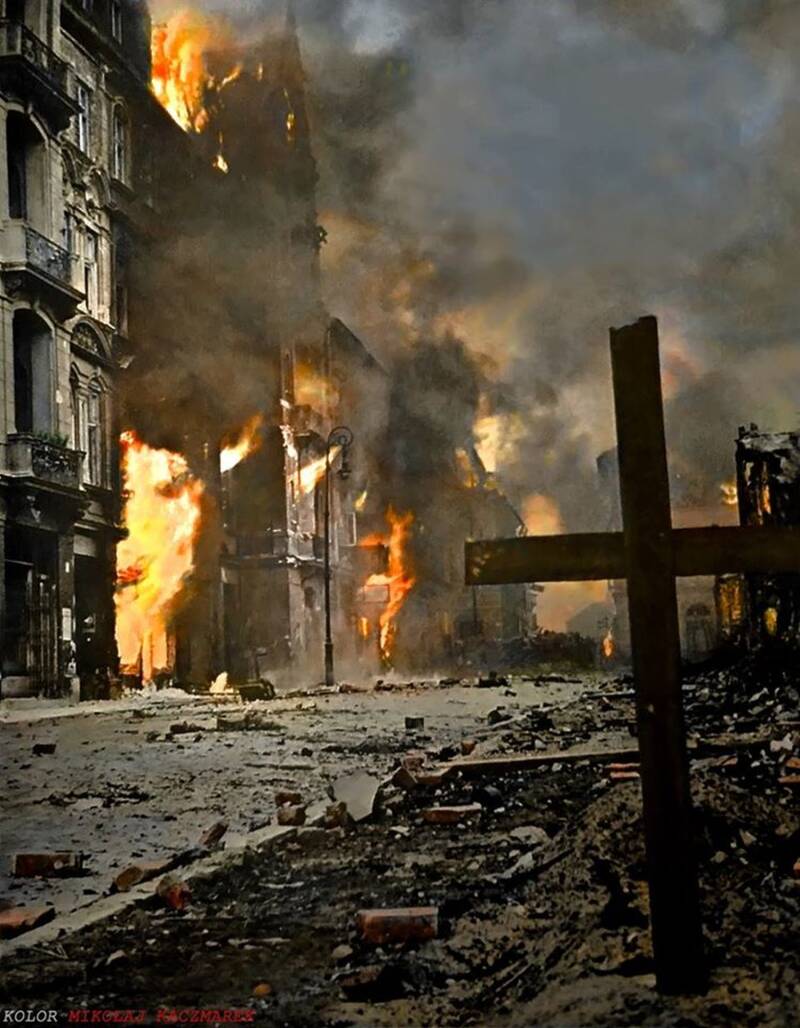

A building takes a direct hit from a German shell during the uprising.

Mikołaj Kaczmarek

A map showing Warsaw on 2nd August, highlighting the gains made by the insurgents but also illustrating the positions of the German strongholds which would cause problems for the Poles throughout the Uprising.

The struggle continues

The first day of the uprising had seen resistance fighters take control of key buildings and landmarks in the city, including the main railway station and the airport. They also set up barricades and fortified positions in the streets to defend against German counterattacks.

The uprising was supposed to only last a few days until Soviet forces arrived, but this ultimately never happened, and the Polish forces were forced to fight on with little outside help. The first two days of fighting in various parts of the city produced the following results:

A captured German Sd.Kfz. 251 from the 5th SS Panzer Division, being used by the 8th "Krybar" Regiment. Furthest right; commander Adam Dewicz "Grey Wolf", 14 August 1944.

Mikołaj Kaczmarek

Medical staff treat wounded insurgents during the Uprising.

Area I (city centre and Old Town): Units captured the majority of their assigned territory but failed to capture areas with strong pockets of German resistance (the Warsaw University buildings, PAST skyscraper, the headquarters of the German garrison in the Saxon Palace, the German-only area near Szucha Avenue, and the bridges over the Vistula).

As a result, they were unable to establish a central stronghold, secure communication links to other areas, or a secure land connection with the northern area of Oliborz via the northern railway line and the Citadel.

Warsaw Uprising in Poland dated August 1944. Old Town Market Place, Dekert's Side. Rare Agfacolor photo made during the fight of Poles against Germans. This photo was not colourised.

Author Ewa Faryaszewska was corporal in Polish Home Army and shot 31 color photos during the Warsaw Uprising.

Ewa Faryaszewska (1920-1944) - Museum of Warsaw

Area II (oliborz, Marymont, Bielany): Units failed to secure the most critical military targets in the vicinity of oliborz. Many units retreated into the forests outside of the city leaving this area in German hands.

Despite capturing the majority of the area around oliborz, the soldiers of Colonel Mieczysaw Niedzielski ("ywiciel") were unable to secure the Citadel and breach German defences at Warsaw Gdask railway station.

Area III (Wola): Units initially took control of the majority of the territory, but suffered heavy losses (up to 30%).

Some units retreated into the woods, while others retreated to the area's east. Colonel Jan Mazurkiewicz's ("Radosaw's") soldiers captured the German barracks, the German supply depot at Stawki Street, and the flanking position at the Okopowa Street Jewish Cemetery in the northern part of Wola.

Home Army soldiers from Kolegium "A" of Kedyw formation on Stawki Street in the Wola District of Warsaw, September 1944.

Public domain

Area IV (Ochota): Neither the territory nor the military targets (the Gesiowka concentration camp, as well as the SS and Sipo barracks on Narutowicz Square) were captured by the units mobilised in this area.

The majority of the Home Army forces retreated to the forests west of Warsaw after suffering heavy casualties. Only two small units of 200 to 300 men, led by Lieut. Andrzej Chyczewski ("Gustaw"), remained in the area and established strong pockets of resistance. They were later reinforced by city centre units.

The Kedyw elite units were able to secure the majority of the northern part of the area and capture all of the military targets there.

They were quickly pinned down by German tactical counter-attacks from the south and west.

Many of Warsaw's buildings were either destroyed or suffered damage during the uprising.

Area V (Mokotów): The situation in this area was dire from the start of the war. The partisans planned to seize the heavily fortified Police Area (Dzielnica policyjna) on Rakowiecka Street and establish a link to the city centre via open terrain at the former airfield of Mokotów Field.

The assaults failed because both areas were heavily fortified and could only be approached through open terrain. Some units withdrew into the forests, while others captured parts of Dolny Mokotów, which was cut off from most communication routes to other areas.

Area VI (Praga): The Uprising began on the right bank of the Vistula, where the main task was to seize the river bridges and secure the bridgeheads until the Red Army arrived. It was obvious that there would be no outside assistance because the location was far worse than the other areas.

After a few minor victories, Lt.Col. Antoni urowski ("Andrzej"forces )'s were vastly outnumbered by the Germans. The fighting ceased, and the Home Army forces were driven underground.

Area VII (Powiat Warszawski): this area included territories outside the city limits of Warsaw. The majority of actions in this area failed to capture their targets.

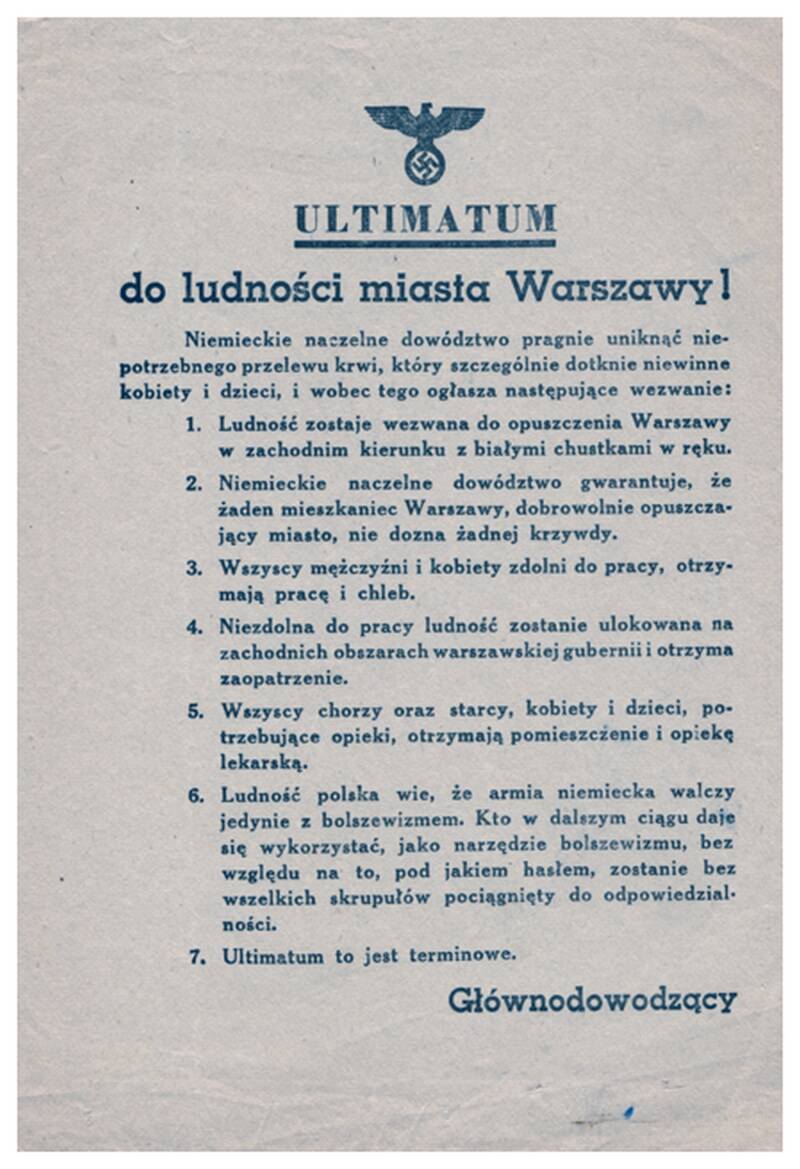

German leaflets were dropped over Warsaw in an effort to encourage Polish civilians to leae t city. Safe passage was promised. The Germans were keenly aware that the Uprising would have little chance of succeeding without the support of the civilian population of Warsaw.

Polish Greatness (Blog): Warsaw Uprising 1944: August 10 - Secret Polish Radio Stations

Insurgents with a captured German Flag.

Timeline of events

| Date | Event |

|---|---|

| 1st July | Plans by the Polish Army are laid out for a resistance and uprising in the Capital City of Warsaw against their German occupiers. Lieutenant-General Komorowski heads up the resistance plans as Commander-in-Chief of the Polish Home Army in Warsaw. |

| 26th July | The Polish government, in exile since the fall of their country to the invading Germans, communicates with the British government for help in staging the uprising. |

| 27th July | The British government promises what it can and this emerges in the form of scattered air drops of weapons and supplies. |

| 31st July | Soviet Army forces close in on German defenders in Warsaw. |

| 1st August | Three Soviet Army Fronts converge on the outskirts of Warsaw, prompting Polish General Komorowski to greenlight the start of the Warsaw Uprising. At 1.50pm in Żoliborz, nearby pl. Wilsona, the first fighting of the Uprising took place. 5pm is recognised as the official start time of the Warsaw Uprising. Upon hearing of news of the uprising, an infuriated Adolf Hitler swears punishment and commits more of his troops to the Polish capital. |

| 2nd August | Insurgents seize strategic points including in the Old Town, Śródmieście, Powiśle and Czerniaków. They also capture two German panther tanks which are they used against their former owners. |

| 4th August | Realizing their chances of victory are slim against the well-trained and well-armed German forces, Polish Authorities once again ask the Allies - including the Soviets - for assistance in maintaining the uprising. |

| 5th August | ‘Black Saturday’ – the mass murder of civilians in Wola. Liberation of Gęsiówka concentration camp resulting in the liberation of 348 inmates. |

| 10th August | German Army reinforcements continue to arrive in Warsaw in an attempt to quell the Polish uprising. |

| 11th August | Sensing complete destruction of Warsaw and its people, the Pope himself appeals to the Allies for help. The Red Army finds themselves some 12 miles outside of Warsaw city centre, having advanced into the Polish suburbs. |

| 16th August | Prioritising his own political interests and plans, Soviet leader Josef Stalin rejects a direct call for aid for the Poles. |

| 20th August | Seizing of the Polish Joint-Stock Telephone Company (the so-called PAST-a) building at 37/39 Zielna street. The insurgents take around 115 German prisoners. However, German Army soldiers now number some 21,300 personnel in Warsaw and their violent response to the uprising has divided the Polish resistance into three distinct groups, all cut off from one another. The Germans begin their final push to crush the Polish response. |

A wounded German receives medical treatment.

A mother and daughter hurry past bomb wreckage in Warsaw.

Children digging out bomb shelters during the Uprising.

A man runs for cover as a building burns fiercely in the background.

Insurgents searching the bodies of dead Germans.

A column of German prisoners, most with their heads shaved by their captors, during the Uprising.

Polish insurgents relax during a lull in the fighting. Note the captured German helmets adorned with Polish colours.

Mikołaj Kaczmarek

Insurgents fighting in the rubble.

A break in the fighting allows insurgents to gulp down some food.

During such traumatic times, it is unsurprising that many turned to their faith to support them. Here a Polish priest reads from his bible.

Insurgents relaxing during a break in the fighting. The snappily dressed chap on the left providing proof that a violent, city-wide rebellion is no excuse for not looking your best.

Curious insurgents look on with interest as one of them assesses a captured German weapon.

A knocked out German self-propelled gun.

Insurgents skirmishing inside the ruins of a building..

Smoke billows out of a building after being struck by a German shell.

A wounded insurgent being helped to a first aid station.

A lone resident flees while a building burns in the background shortly after a German attack.

| Date | Event |

|---|---|

| 25th August | SS Obergruppenfuhrer Erich von dem Bach-Zelweski details the final German push and the Germans begin their counter-offensive against the remaining Pole units. |

| 1st September | German assault on the Old Town. The insurgents evacuate through canals to Śródmieście and Żoliborz. |

| 2nd September | During the early hours of the morning, tank shells smash Sigismund’s Column. The Germans capture the Old Town. Fighting in other parts of Warsaw continues. |

| 10th September | The Red Army begins an offensive from the Praga bank of the Vistula. |

| 16th September | Pressured by the Americans and British, Stalin reluctantly agrees to offer some assistance to the Poles and delivers a meager air drop of arms consisting of just fifty pistols and a pair of machine guns. On the same day, Polish Army units fighting alongside the Soviet Army make a depserate attempt to support their comrades in Warsaw, going against the orders of Soviet High Command. |

| 17th September | Under the command of Lieutenant-Colonel Zygmunt Berling, the 1st Polish Army forces engage the Germans in Warsaw but are ultimately driven back in retreat. |

| 18th September | American B-17 bombers land at Poltava, now under Soviet control, to refuel. Onboard are arms and supplies meant for the Polish resistance. 107 B-17s manage to make the biggest airdrop of weapons, ammunition, food and medicine of the Uprising. Unfortunately, the insurgents managed to pick up only 20 percent of what was dropped.Josef Stalin then refuses further Allied use of his forward airfields to resupply the Polish insurgents. |

| 21st September | For his actions in disobeying Soviet Army orders, Lieutenant-Colonel Zygmunt Berling is stripped of his army command. |

| 25th September | American air drops deliver their much-needed cargo to the Polish resistance below. However, the drop zones are in firm German control and supplies are captured soon after landing. |

| 1st October | A daytime ceasefire is agreed allowing many Polish citizens to evacuate the city. |

| 2nd - 3rd October | Polish General Komorowski, sensing total defeat imminent, orders his Polish insurgents to surrender to the Germans. The Uprising fails. The capitulation order is signed in Ożarów, bringing fighting in Warsaw to an end. The order grants the insurgents full prisoner-of-war status protected under the Geneva Convention, and offers protections to civilians in the city against liability for violating German regulations. During the following days, the insurgents are taken from the city to prisoner-of-war camps. Civilians from Warsaw, on the other hand, are sent to transit camps in Pruszków, Ursus, Włochy and Ożarów. Unfortunately, over 100,000 of them are sent for forced labour in the Reich and another several dozen thousand to concentration camps where many will ultimately perish. |

An insurgent armed with a flamethrower during the uprising.

The units of the Directorate of Sabotage and Diversion, or Kedyw, formed an additional area within the Polish command structure, guarding the headquarters and acting as a "armed ambulance" thrown into the battle in the most dangerous areas.

These units, along with the units from Area I, were the most successful during the first few hours of the battle.

The airfields of Okcie and Mokotów Field, as well as the PAST skyscraper overlooking the city centre and the Gdask railway station guarding the passage between the centre and the northern borough of oliborz, were among the most notable primary targets that were not taken during the early stages of the uprising.

The insurgents made good use of makeshift barricades throughout the Uprising.

German prisoners standing in front of the wall of the former Jewish ghetto on Bonifraterska Street.

75 Breathtaking Photographs Describe the Warsaw Uprising of 1944 ~ Vintage Everyday

Polish insurgents move stealthily through a courtyard.

A German officer and Polish insurgent discuss a temporary ceasefire to allow for the retrieval of dead and wounded.

A map showing blocks of houses held by the Polish Underground Army between the 24th of August and the 15th of September at 1:50,000 scale. The maps also show streets that were either fully or partly under the control of German forces. As can be seen from the image, in some cases the streets held by the Germans ran next to — and in one case through — Polish-held areas.

Overall, the Poles took control of most of central Warsaw, but the Soviets ignored Polish radio contact and did not advance beyond the city limits. Germans and Poles continued to fight in the streets.

The eastern bank of the Vistula River, opposite the Polish resistance positions, had been taken over by Polish troops fighting under Soviet command by 14 September; 1,200 men made it across the river, but they were not reinforced by the Soviet Red Army.

German prisoners captured during the Uprising. The ferocity of the fighting can be seen in their expressions.

Polish Insurgent next to the burnt Italian built but German owned Carro Armato M13 / 41 tank. Warsaw, 23 August 1944.

Mikołaj Kaczmarek

Fighting in the Old Town

Some of the fiercest fighting took place in the Old Town district of Warsaw. For nearly a month, the insurgents defended the northernmost point of the Old Town, the Polish Security Printing Works.

The battle scars on the fence around the site can still be seen today. The St. Kazimierz Church of the Sisters of the Holy Sacrament housed an insurgent hospital. Over 1000 people died in the church during one air raid.

Insurgents carrying a dead comrade.

Insurgents attacking from the Victoria Hotel on Jasna Street. The hotel was captured early on in the Uprising and soon became their headquarters.

German soldiers captured during the uprising.

Mikołaj Kaczmarek/Warsaw Rising Museum

On 13th August 1944, the Germans placed a Borgward explosive charge carrier at the barricade where Podwale Street meets Castle Square.

The insurgents mistook it for a small tank and drove it recklessly around Old Town. The vehicle exploded around 6 p.m., killing approximately 500 people.

From the 21st to the 27th of August there was a fierce battle for the St John the Baptist cathedral.

The church was completely destroyed as a result of the bombing and a massive attack by German infantry.

A tank track fragment is still embedded in the cathedral wall, possibly from a 'Goliath' (light explosives transporter) or another nearby explosion. Such was the ferocity of the fighting; it is hard to tell.

Transporting a wounded insurgent.

Photo taken in the garden in the back of the property at Mazowiecka Street.

Mikołaj Kaczmarek

The impressive Column of Sigismund III Vasa - the oldest and highest secular monument, was erected in 1644 on Wadysaw IV's initiative in honour of his father, Zygmunt III Waza, who relocated the capital from Krakow to Warsaw. Three hundred years later, during the fierce German attack on the Old Town, the monument was destroyed. The original 17th-century column and the one destroyed during the Uprising are both located near the Royal Castle.

The Arsenal was strategically important during the Uprising because it defended access to the Old Town from the west. Another historical event occurred here more than a year before the Uprising. During Operation Arsenal, over 20 prisoners being transported from the Gestapo headquarters on Szucha to Pawiak were freed. The building was bombed by the Germans on August 23, 1944. It was rebuilt after the war using surviving battle fragments and now houses the State Archaeological Museum.

German prisoners being escorted by the insurgents.

Insurgents running towards a burning building in the courtyard of the Police Headquarters (Krakowskie Przedmieście 1) during an assault on the Police Headquarters and the Holy Cross Church on 23 August 1944.

2013 © Warsaw Uprising Museum.

On 6th September, the Germans sent two "goliaths" inside Holy Cross Church. The vault of the church collapsed as a result of the explosion, and the figure of Christ standing on the steps outside bearing a cross with the inscription 'Sursum corda' (Lift up your hearts) fell. Those of a religious nature might have felt this was an ominous sign.

City centre

The centre of Warsaw was also the scene of heavy fighting. During the Uprising, a Home Army field hospital operated in the city centre. Both insurgents and German soldiers were helped by the Sisters of Charity who tended to the wounded. A bullet-riddled hospital fence serves as a memorial to the Uprising.

Many locals sought refuge in the basement of the pre-war chocolate factory building of Emil Wedel. A radio station was also broadcast from here. There is a stylish company store and chocolate cafe today, just as there was before the outbreak of the war.

Insurgents sheltering behind rubble during the Uprising. The damage done to the buildings of Warsaw often worked in favour of the insurgents.

The Palladium cinema opened in 1937 and despite the destruction around it, survived the war, and remained in operation until 2000. During the occupation, the Germans renamed the area Helgoland. When the insurgents took over the cinema, they showed news footage titled Warsaw is Fighting. A music club and a theatre are currently operating here.

The Prudential building was the tallest structure in Poland and one of the tallest in Europe before the war. It was captured by insurgents on 1st August, and a Polish flag sewn from a sheet and a red pillowcase was hung from its roof. It was heavily damaged during the battle and rebuilt in a socialist-realist style. The building is currently home to a hotel.

Warsaw city centre suffered extensive damage during the Uprising.

Throughout the uprising, many Polish civilians remained in the city and attempted to carry on with their daily lives - as best as they could.

Polish insurgents wearing captured German helmets fire from within a fortified building.

Building of the Polish Joint-Stock Telephone Company - PAST - During the Uprising, the building was strategically important due to its location and height (the second highest in pre-war Warsaw). It was in the hands of the Germans until 20 August 1944, when they could easily observe and shell northern areas of the city centre.

The insurgents finally took control of the building after fierce fighting. It was one of the Uprising's most significant military victories. The 'Fighting Poland' anchor symbol was placed on the roof to commemorate those events.

Insurgents leading German soldiers out of a building of the Polish Telephone Joint-Stock Company on Zielna 37/39 following its capture on 20 August.

2013 © Warsaw Uprising Museum.

Liberation of Gęsiówka concentration camp

The "Zoka" scouting battalion of the Home Army's Radosaw Group, led by Ryszard Biaous and Eugeniusz Stasiecki, attacked the Gsiówka concentration camp, which was being liquidated by the Germans, on 5 August 1944, early in the Warsaw Uprising. Magda, one of two Panther tanks captured by Polish insurgents on 2 August and assigned to Zoka's newly formed armour platoon led by Wacaw Micuta, supported the assault with its main gun. The majority of the camp guards were killed or captured during the one-and-a-half-hour battle, though some fled toward the Pawiak prison.

Polish soldiers of tank platoon "Wacek" of ""Zośka" Battalion on a captured German Panther tank around Okopowa Street.

From the left: Mieczysław Kijewski "Jordan", Eugeniusz Romański "Rawicz", Jan Myszkowski-Bagiński "Bajan" and Zdzisław Moszczeński "Ryk" (backward).

Public domain

The attack killed only two Polish fighters. 348 able-bodied Jewish prisoners were saved from certain death - the Germans had retained them as slave labour after the liquidation of the Warsaw Ghetto in 1943 and were left behind after the evacuation of most of the Gsiówka camp's inmates in July 1944.

Many of the Jewish prisoners joined the insurgents, and the majority of them were killed in the next nine weeks of fierce fighting, as were the majority of their liberators (the "Zoka" battalion lost 70% of its members in the Uprising).

Gdansk Railway station

The battle for Gdansk Railway station is regarded as the bloodiest of the Uprising. During two nights from the 20th to the 22nd of August, nearly 500 Home Army soldiers were killed in insurgent attacks. A sculpture depicting a young woman bending over an insurgent grave commemorates the events of those days today.

The ruins of the train station. Warsaw suffered extensive damage during and after the uprising, losing a high percentage of its buildings.

Atrocities

Numerous atrocities occurred during the Uprising. The most infamous was the Wola massacre which was the systematic killing of between 40,000 and 50,000 Poles in Warsaw's Wola neighbourhood by the German Wehrmacht and fellow Axis collaborators in the Azerbaijani Legion, as well as mostly-Russian RONA forces, from 5th to the 12th August 1944. Adolf Hitler directed the massacre to kill "anything that moves" in order to put an end to the Warsaw Uprising soon after it began.

Elsewhere, in Mokotów, SS units commited numerous murders of civilians in Fort Mokotowski and Rakowiecka Street. Over 600 prisoners were also murdered in the Mokotów prison.

The Ochota Massacre was a wave of German-ordered mass murder, looting, arson, torture, and rape that swept through the Warsaw district of Ochota from August 4 to August 25, 1944, during the Warsaw Uprising. The Nazi collaborationist S.S. Sturmbrigade R.O.N.A., the so-called "Russian National Liberation Army," led by Bronislav Kaminski, was the main perpetrator of these war crimes.

Life during the uprising

Warsaw had a population of approximately 1,350,000 people in 1939. At the start of the Uprising, over a million people were still living in the city.

During the first weeks of the Uprising, people in Polish-controlled territory attempted to recreate the normal day-to-day life of their free country.

Cultural life was vibrant among both soldiers and civilians, with theatres, post offices, newspapers, and other similar activities.

Polish Scouts boys and girls worked as couriers for an underground postal service, risking their lives every day to transmit any information that could help their people.

In total, 150,000 letters were delivered during the Uprising..

Young insurgents gather during a quieter moment. If it was not for their uniforms, it would resemble many typical social meeting of twentysomethings.

Near the end of the Uprising, a lack of food and medicine, overcrowding, and an indiscriminate German air and artillery assault on the city exacerbated the civilian situation.

Booby traps, such as thermite-laced candy pieces, may have also been used to target Polish youth in German-controlled areas of Warsaw.

Overall, there were 123 civilian and 109 military hospitals and dressing points operating during the uprising.

An elderly Warsaw resident. His expression speaks for many of his fellow residents.

During a quieter moment, insurgents pose for a photo.

Because the Soviets were supposed to end the uprising in a matter of days, the Polish underground did not anticipate food shortages. However, as the fighting continued, the city's residents faced hunger and starvation.

On 6th August, Polish units recaptured the Haberbusch I Schiele brewery complex on Ceglana Street, marking a significant breakthrough.

From then on, Warsaw residents relied heavily on barley from the brewery's warehouses.

Every day, thousands of people organised into cargo teams reported to the brewery for bags of barley, which were then distributed throughout the city centre.

The barley was then ground in coffee grinders and boiled with water to make spit-soup (Polish: spit-soup).

The "Sowiński" Battalion managed to hold the brewery until the end of the fighting.

Eventually, there were 178 communal kitchens and feeding points operated in the city during the Uprising.

Insurgents carrying sacks of Barley - the availability of this grain helped stave of starvation for the Polish population.

Wherever possible, life carried on as normal during the uprising.

Another major issue for both civilians and soldiers was a lack of water. By mid-August, the majority of the water conduits were either broken or filled with corpses. Furthermore, the main water pumping station remained under German control. The authorities ordered all janitors to supervise the construction of water wells in the backyards of every house in order to prevent the spread of epidemics and provide people with water.

The Germans blew up the remaining pumping stations on Koszykowa Street on September 21st, leaving public wells as the only source of potable water in the besieged city. By the end of September, the city centre had over 90 operational wells.

Those not in the front line could still help the Uprising in other ways. This insurgent is cleaning and maintaining an assortment of weapons used by the Polish fighters.

Insurgents eating in a rudimentary field kitchen. Despite initial food shortages, the capture Haberbusch I Schiele brewery and its supplies of barley helped stave off starvation for the Polish.

Polish media

Prior to the Uprising, the Home Army's Bureau of Information and Propaganda established a group of war correspondents.

The group, led by Antoni Bohdziewicz, produced three newsreels and over 30,000 metres of film tape to document the struggles.

On 13th August, the first newsreel was shown to the public at the Palladium cinema on Zota Street. Aside from films, dozens of newspapers were published from the beginning of the uprising.

A few previously underground newspapers began to circulate openly. The government-run Rzeczpospolita Polska and the military-run Biuletyn Informacyjny were the two main daily newspapers.

Several dozen newspapers, magazines, bulletins, and weeklies were also published on a regular basis by various organisations and military units. In total:

- Almost 150 press titles were published.

- Around 28,000 copies of the ‘information bulletin’ were distributed.

- About 30,000 metres of film was shot.

Early and late editions of the Armia Krajowa's "Biuletyn Informacyjny" ("Information Bulletin") published on 2nd August 1944. Over 130 different newspapers and periodicals were published in Warsaw during the uprising.

Polish underground radio provided a vital lifeline to the outside world during the Uprising.

Polish Greatness (Blog): Warsaw Uprising 1944: August 10 - Secret Polish Radio Stations

Jan Nowak-Jeziorański. Known as the "Courier from Warsaw" he spoke on the resistance radio.

Public domain

The military ran the Byskawica long-range radio transmitter, which was assembled in the city centre on 7th August, but it was also used by the recreated Polish Radio beginning on 9th August.

It broadcast news and appeals for help in Polish, English, German, and French, as well as government reports, patriotic poems, and music, three or four times a day.

Between 8th August and the 4th October, 1944, the 'Lightning' was broadcast four times per day in Polish, English, and German. Typical programmes included reports from besieged Warsaw, appeals for help, combat communiques from the Home Army, and patriotic songs and poems.

'Lightning' transmissions could be heard as far away as New York City.

Insurgent handing out copies of the information bulletin.

http://warsawrising.eu/

German planes were constantly looking for the "Lightning's" transmitter. A 1,500 kilogramme shell smashed through the radio station's six floors and landed in the basement without exploding.

The Germans broadcast their 'Polish' radio station on the same frequency as the 'Lightning,' attempting to provide false information and orders to the insurgents.

It was the only radio station of its kind in German-occupied Europe.

Jan Nowak-Jezioraski, Zbigniew Witochowski, Stefan Sojecki, Jeremi Przybora, and John Ward, a war correspondent for The Times of London, were among those who spoke on the resistance radio.

Correspondents actually filmed much of the Uprising as it happened - at great risk to themselves - the results of which can be seen on this very page.

Soviet Betrayal?

The lack of air support for the Uprising from the Soviet air bases - located around five minutes flying time away - prompted accusations that Joseph Stalin tactically halted his forces in order to allow the operation to fail and the Polish resistance to be crushed.

Up until the 10th of September, 1944, the Soviet armies, which were massed just a few kilometres outside Warsaw, were completely impassive, allowing the Luftwaffe to destroy the city with impunity. According to Soviet propaganda, the uprising was described as a fracas that was obstructing Red Army operations.

Troops of the 1st Polish Army in 1944.

From 15th to the 23rd September, when the uprising was in its late stages, Polish general Zygmunt Berling led a rescue effort that involved crossing the Vistula and establishing a bridgehead on the west bank, with his First Polish Army (under the overall command of the Soviets) on the east bank and the Praga district of Warsaw already secured.

The failed operation, which was possibly carried out without full consultation with Berling's Soviet military superiors, resulted in heavy Polish Army casualties and probably resulted in Berling's dismissal from his post shortly afterwards.

Warsaw airlift

Winston Churchill pleaded with Stalin and FDR to assist Britain's Polish allies, but to no avail. Then, in an operation known as the Warsaw Airlift, Churchill sent over 200 low-level supply drops by the Royal Air Force, the South African Air Force, and the Polish Air Force under British High Command.

Later, after obtaining Soviet air clearance, the United States Army Air Force launched one high-level mass airdrop as part of Operation Frantic, with 80% of the supplies landing in German-controlled territory.

Warsaw Uprising:American Boeing B-17 Flying Fortress planes leaving Warsaw and heading East after air drops on September 18. Wisła river is visible, as well as Wilanów Palace end gardens, which can be seen at upper/left part of the image.

Public domain

The beginning of the end

The Germans drove the insurgents out of Powisle between 3rd and 6th September, and the battle for Czerniaków began on 12th September.

Only on the 10th September did the Russians launch an offensive against the Germans in the Warsaw region.

Some supplies were airdropped, and Soviet fighter planes began chasing German bombers above Warsaw. This convinced the Home Army leadership to call off the initiated capitulation talks.

In the circumstances, the half-hearted Soviet assistance to the Uprising contributed to the prolongation of the conflict, which was only weakening both the Germans and the Poles to Soviet advantage.

Insurgents manning a machine gun during the Uprising.

From the 13th to the 15th of September, Soviet armies and subordinated detachments of the 1st Polish Army pushed the Germans out of the city's right bank. After a long period of waiting for Soviet cooperation, an air drop operation involving 107 American Flying Fortresses landed in Ukraine on 18th September.

Between the 16th and the 19th of September, detachments of the 1st Polish Army landed in several locations on Warsaw's left bank (in Czerniaków, Powisle, and Zoliborz), but these bridgeheads were unsustainable due to insufficient Russian support.

A young Polish girl tending a grave during the uprising.

Mikołaj Kaczmarek/Warsaw Rising Museum

The last groups of Home Army insurgents and 1st Polish Army soldiers fought in Czerniaków until 23rd September, with some escaping through the sewers or across the Vistula.

After seizing control of the Sadyba and Sielce sub-districts in the city's south, the Germans launched an offensive against the insurgents in the Upper Mokotów area on 24th September.

On 26th September, it was ordered that it be evacuated through the sewers. The last defenders surrendered a day later.

On 29th September, a strong German attack against Oliborz (led by the 19th Panzer Division) began, leading to the district's surrender the next day.

Capitulation

The two-month battle for Warsaw was a nightmare for the city's residents, especially the hundreds of thousands of civilians who sought refuge in the cellars.

Tens of thousands of dead and wounded, illnesses, a lack of water, and hunger were the realities of insurgent Warsaw's final weeks.

In the face of certain defeat, the Commander-in-Chief of the Home Army, General Tadeusz Bór-Komorowski, who was also the Commander-in-Chief of the Polish Armed Forces as of 30th September, nominated General Leopold Okulicki (pseudonym "Niedzwiadek") as his successor in the Polish underground on 1st October, 1944.

On the night of 2nd and 3rd October, a cease-fire agreement was signed in Ozarów, near Warsaw. Along with General Bór Komorowski, over 15,000 insurgents were captured.

General “Bór” Komorowski Leading his men into captivity after the Warsaw Uprising, 5th October 1944.

Aftermath

Although the precise number of casualties is unknown, it is estimated that approximately 16,000 members of the Polish resistance were killed and approximately 6,000 were severely injured.

Furthermore, between 150,000 and 200,000 Polish civilians died, the majority as a result of mass executions. German house-to-house clearances and mass evictions of entire neighbourhoods exposed Jews being harboured by Poles.

Over 2,000 to 17,000 German soldiers were killed or went missing. Approximately 25% of Warsaw's buildings were destroyed during the urban combat.

Warsaw was devastated during the uprising.

Following the surrender of Polish forces, German troops levelled an additional 35% of the city block by block.

With earlier damage from the German invasion of Poland in 1939 and the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising in 1943, over 85% of the city was destroyed by January 1945, when the course of events on the Eastern Front forced the Germans to abandon the city.

A Verbrennungskommando (slave labour) subordinated to Waffen-SS, setting fire to buildings in Warsaw after the end of the Warsaw Uprising in 1944.

Mikołaj Kaczmarek

A Polish civilian surveys the utter devastation around her.

A group of Polish civilians who did not form part of the insurgency against the Nazis being herded out of the capital’s Ochota district.

Warsaw Rising Museum

The Warsaw Uprising Monument in Krasińskich Square, Warsaw.

Further reading

Colourisation

Many of the incredible colourised pictures you seen on this page were created by. Mikołaj Kaczmarek. More of his amazing work can be seen on his Facebook page.

Sources:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Warsaw_Uprising

Mikołaj Kaczmarek

Warsaw Rising Museum

http://warsawrising-thefilm.com/multimedia/

http://callumwall.co.uk/scouts-in-the-warsaw-rising

Przemyslaw Bieganski

https://www.facebook.com/worldwarincolor

https://www.historynet.com/warsaw-rising-hope-and-betrayal/?msclkid=2b729342ce5511ec9db4b051b7869cb8

https://blogs.bodleian.ox.ac.uk/maps/2013/02/08/139/

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/User:Halibutt

Ewa Faryaszewska (1920-1944) - Museum of Warsaw

https://www.vintag.es/2020/01/colorized-warsaw-uprising.html#more

http://thirdreichcolorpictures.blogspot.com/2010/03/generalfeldmarschall-walter-model.html

sovfoto/universal images group/REX/Shuttershock

Bundesarchiv. bild 1011-695-0407-26

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/User:Lonio17

http://warsaw-uprising.webflow.io/

https://www.tumblr.com/tagged/stg44?page=44&sort=top

https://warsawtour.pl/en/project/warsaw-rising-museum-2/

https://www.vintag.es/2020/01/colorized-warsaw-uprising.html

https://live.staticflickr.com/8282/7822327808_a137d0dfa4_b.jpg

https://www.nevingtonwarmuseum.com/warsaw-uprising.html

Warsaw Rising Museum

https://archimaps.tumblr.com/tagged/war/page/3

Marek Jan Chodakiewicz

https://www.iwp.edu/articles/2002/04/01/the-warsaw-uprising-1944/

https://www.polskieradio.pl/313

Bundesarchiv, Bild 101I-280-1075-11A / Wehmeyer / CC-BY-SA 3.0

https://www.nationalww2museum.org/war/articles/women-and-children-1944-warsaw-uprising

https://polishgreatness.blogspot.com/2011/08/warsaw-uprising-1944-august-10-secret.html

https://wyborcza.pl/alehistoria/7,121681,17369282,ucieczka-stanislawa-mikolajczyka.html

Getty Images

Dr Tadeusz Kondracki

https://polishgreatness.blogspot.com/2011/08/warsaw-uprising-1944-august-31-polish.html

https://www.holocausthistoricalsociety.org.uk/contents/polandresists/warsawuprising1944.html

https://www.secondworldwarhistory.com/warsaw-uprising.php

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/G%C4%99si%C3%B3wka